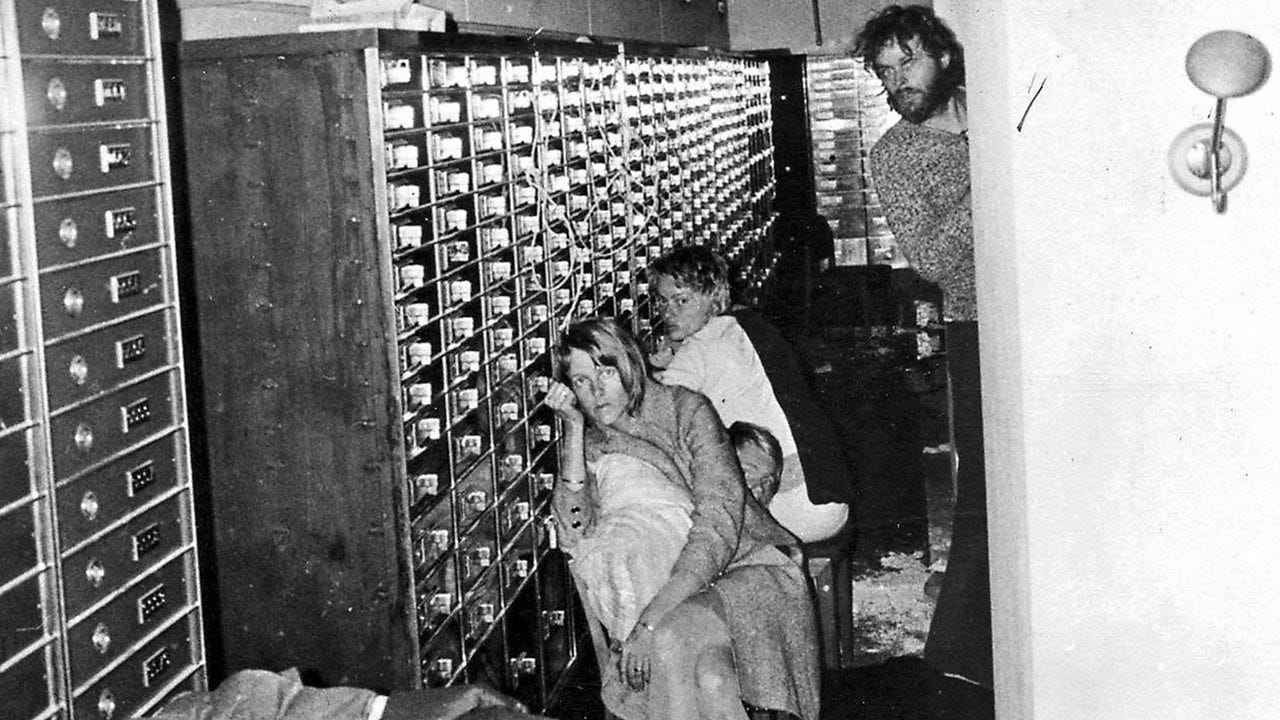

In August 1973, a convict on parole held four bank employees hostage in Stockholm, Sweden. He demanded the Swedish government release his friend from prison in exchange for the hostages.

Six days later, the hostages were released and the captor arrested. Later, they refused to testify against the man who held them hostage and even raised money for his defense.

In interviews, the hostages indicated that they felt the police response was inept and that they feared the police more than the criminal.

A Swedish psychiatrist was asked to consult on the hostages’ abnormal behavior. He described their reactions as a result of being brainwashed by their captor and called it Norrmalmstorgssyndromet or “The Norrmalm Square Syndrome” after the location of the bank. Outside of Sweden, this behavior later became known as “Stockholm Syndrome.”

The captor admitted that he also became attached to the hostages:

“It was the hostages’ fault. They did everything I told them to. If they hadn’t, I might not be here now. Why didn’t any of them attack me? They made it hard to kill. [The police] made us go on living together day after day, like goats, in that filth. There was nothing to do but get to know each other.”

Despite its popularity in our modern vernacular, Stockholm Syndrome is very rare in hostage situations. Today, psychologists suggest that the hostage’s outpouring of support was an anomaly and have instead proposed changing the term to “appeasement.” Appeasement describes a strategy adopted by those in abusive situations who attempt to keep their captor happy through positive reinforcement.

These two concepts – Stockholm Syndrome and appeasement – swirl in my mind when a patient is unfailingly chipper during treatment. Lack of complaint or questions raises a red flag. As someone who regularly confronts the unfair hands dealt to my fellow humans, I view optimism with suspicion. It is impossible for me to believe that a generally aware person is diagnosed with cancer, undergoes treatment and has few, if any concerns, or questions.

My husband calls this negativity. I call it being realistic.

I narrow my eyes and wonder: how much fear is hidden behind that smile? Are you truly “ok” as you profess or is this an effort to appease me?

It’s hard enough to be honest with loved ones about our suffering, how much harder it must be to share with the one who is prescribing it.

Are you putting on a happy patient routine for me?

I am relieved when a nurse, radiation therapist, social worker, counselor or other healthcare team member share that a patient opened up to them. The information comes to me secondhand but at least I know. You can’t appease everyone.

A chaplain told me, “Many times patients came into my office, shut the door, and said they couldn’t talk about their reality, their fears, because doing so would upset their families. And even doctors. Patients felt they had to make their doctors feel better and successful by staying positive.”

She shared an example of when she was asked to accompany a doctor on his normal hospital rounds. They stopped outside the room of a woman with advanced lung cancer. The oncologist asked her to go in after him to see if she would learn anything he hadn’t. After seeing the patient, the doctor came out and said the patient seemed positive and upbeat. My friend went in next. “What I learned in my conversation with her was that she felt she had to stay positive because she didn’t feel her doctor was comfortable talking with her about dying. And she knew she was dying. If doctors would use chaplains, they might learn a lot more about their patients.”

I knew a female surgeon who had to give up practicing due to debilitating neuropathy from chemotherapy. She couldn’t feel her hands, so she had to stop using them. I asked her why she hadn’t told her oncologist about her symptoms during treatment. “Because then she would have stopped my chemotherapy,” this brilliant woman answered, “and I didn’t want that. I wanted to live.”

Are you a patient or a hostage? How do we define this situationship that we are in?

I could fill pages with the outpouring of support and love that I have received from patients, their families and caregivers. From delicate handcrafted items to horse-related paraphernalia, you all somehow manage to think of me before you traipse in for another appointment. Through ropey secretions and a painful, sunburned neck. Or frequent nocturnal trips to the bathroom from an irritated prostate.

I received a kind note from a widow thanking me for caring for her wife and “treating her like a person” during the last year of her life. And a hug from a gruff, wrinkled construction worker who refused to see any other doctor during his treatment after I shared the story of trying to buy my husband a welder for Christmas.

“You saved my life!” some exclaim sweeping me in generous hug.

It is simultaneously joyous and difficult to watch you walk out the clinic door for the last time, the break-up inevitable and the promises to keep in touch fading as the elevator doors close.

I see it in your eyes too. You who have been such a good patient and believe that I will pronounce that you are definitely, beyond a doubt cured, long to hang on as well.

Your heart yearns to return to your outside-the-cancer-center-life, but there is a part of you that knows that only the people within these walls truly understand. We have, after all, lived like goats together in the crappy pigsty of cancer.

Last Valentine’s Day Post:

A Conversation with My Husband

People are often surprised that I’m not married to a doctor. I’m not sure why. Maybe they think that my schedule must be crazy, and another physician would better understand?

On my mind…

Find your joy. You don’t have to be good.

Such a great essay - man you have killer insight as to how your patients relate to you. I think it’s great that we patients can indeed “vent” to staff and still keep our docs on a plane that, frankly they don’t deserve. But I need to at times so I can get thru whatever surgery I have going (remember I’ve had 62 surgeries over my 60 years!). I remember my surgeon asking my wife if I ever complained. I rarely do but when I do it’s dark. So I need that people pleasing skill from time to time to be able to get thru to make my doc glad I was a patient. It’s a silly thing, I know, but I’ve survived some incredibly close calls. Thank you as always for your perspective. By the way, anytime my addictions patients would say, “you saved my life…“ I would always remind them that God save their lives and I got to be there to watch it happen. It’s very empowering for them. And kept me off the pedestal as needed! 😉

When I was in the hospital for a month to undergo a stem cell transplant (for MDS), several of my nurses teased me about being so upbeat. I wasn't feeling too good, but complaining about it made me feel worse. When it was time to leave the hospital, I was terrified because I wasn't ready to care for myself. Daily trips to the clinic for blood draws and infusions helped me adjust. But as those have dwindled off, I do kind of miss the intense attention. I thought I was crazy!