The 7 Cs of Effective Doctor-Patient Communication

It's more than writing down questions before your appointment.

“Think about your questions before you go.”

“Take someone with you.”

“Ask the doctor if you can record the conversation.”

“Write everything down.”

We have all heard these nuggets of wisdom, doled out by well-meaning supporters.

And yes, these are all good suggestions. Classic patient advocacy training focuses on documenting and processing the flood of information coming at patients during an initial consultation. Those who follow only these “rules”, however, will face an information tsunami holding only a teacup.

More information and increasingly complex care have led to drastic changes in the information exchange that must occur. What worked before in a time of simple treatments and less information does not work now. In addition, time constraints and physician shortages may limit our time together.

So, what is a patient to do?

Tomorrow I am speaking at a two-day symposium in Raleigh. Patients, caregivers, doctors and advocates are gathering to talk about small-cell lung cancer. As I reviewed the retreat agenda, I was struck by how complex the treatment of small cell lung cancer had become.

When I began my career twenty years ago, most patients with small-cell lung cancer presented with incurable disease and after a brief treatment course, entered hospice care. For the lucky few where cancer was found early, treatment was straightforward, and options were limited. The entirety of the small cell lung cancer treatment paradigm could be covered in an hour-long lecture at a professional meeting.

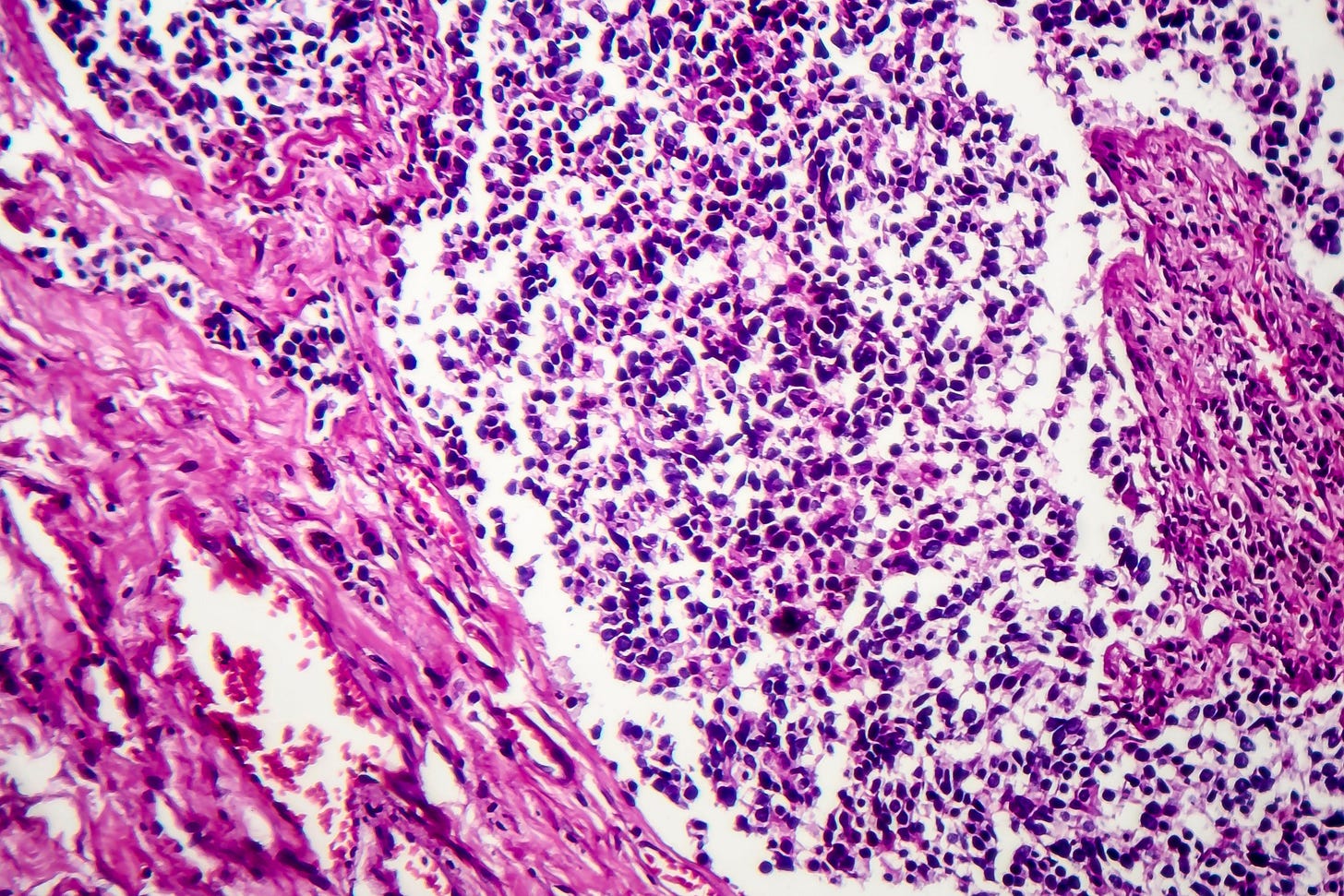

Like many cancers, our understanding of small cell lung cancer has evolved. Rather than using crude descriptions like the comparative size of the cells (“small” or “non-small”), gene mutations drive choices for systemic treatment. Research supports the use of targeted brain radiation rather than the more antiquated whole brain approach which left patients with long term, incurable cognitive side effects.

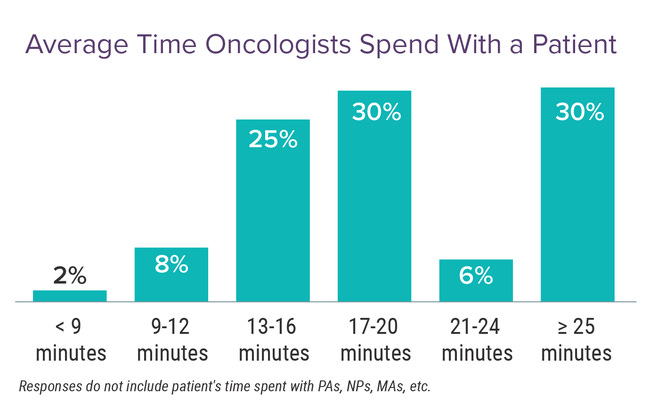

And yet the time that oncologists have to explain this increasing treatment complexity has not kept pace. Oncologists are typically allotted 60 minutes for a new patient appointment. That time has been the same since I started my residency almost 20 years ago. In some health systems, it has shrunk to only 30 minutes.

Wait times for a new patient consultation have also ballooned. Texas Oncology, for example, reported a 2-3 week wait for a first appointment. By the day rolls around, pressure to start treatment ASAP has peaked.

Merriam Webster defines communication as “a process by which information is exchanged between individuals through a common system of symbols, signs or behavior.” Another definition said “Communication is the active process of exchanging information and ideas. This involves both understanding AND expression.”

In medical school, doctors are exposed to techniques like reflective listening and motivational interviewing. What I am less familiar with is how patients learn to talk to their doctors. How do you know what to say to us? And if you don’t get the information you need, how do you prepare to do a better job communicating next time? Or do you just chalk it up to a physician isn’t a great communicator and go looking for someone else?

Doctor-patient communication involves not only speaking to each other but also listening to gain more information about how the other person thinks or feels. This communication is critically important when determining cancer treatment, yet I’m not sure anyone tells patients that this is what we need to accomplish in 60 minutes.

In his 2015 best-selling book How Doctors Think, Dr. Jerome Groopman argued that by understanding how their doctors make decisions, patients could modify their behavior to receive better care. Forcing doctors into longer conversations, open-ended questions, and limitless curiosity were the keys to better outcomes. Groopman wrote,

“Certainly the primary imperative of a physician is to be skilled in medical science, but if he or she does not probe a patient's soul, then the doctor's care is given without caring, and part of the sacred mission of healing is missing.”

Perhaps. But is it only the doctor who must come prepared?

In the introduction to her book Your Life Depends on It: What You Can Do to Make Better Choices About Your Health, Cambridge decision scientist Dr. Talya Miron-Shatz outlines the importance of patient engagement in their healthcare:

We all make health and medical choices every single day. We choose to take a vitamin supplement, go for a run despite a sore tendon, forgo birth control pills, or have chemotherapy after cancer surgery. The more important those decisions are, the more vulnerable we are, and the tougher choosing becomes. This is why we need to build up skills to deal with these choices.

We need to know how to ask the right questions, distinguish information from misinformation, and make the best health choices for ourselves and our loved ones.

Drs. Groopman and Miron-Shatz made excellent points in their book, but I didn’t walk away with practical tips that I could use in my talk. I finally found a website where a contractor for the United Kingdom’s National Health Service described the “7 Cs of Communication.” A little cheesy, yes, but the more I read, the more it felt like something tangible that I could share with you and the lung cancer conference attendees.

According to these experts, effective communication must be: clear, concise, concrete, correct, coherent, complete and courteous.

Clear

Use specific language when telling your story or asking questions. Review with a friend. Is anything ambiguous? Consider your goals for treatment and be able to articulate more than “I value quality over quantity of life.” Think deeply about what you want from your treatment and educate yourself on if those goals are possible by reading reputable sources.

Concise

Ask your questions, tell your story and share your feelings succinctly. Identify 3 or 4 key fundamental questions that you want to ask. I can’t count the number of times that a patient chats about their grandkids for the first 15 minutes of a follow-up visit, only blurting out their new (and sometimes very concerning) side effects as my hand is on the door to leave. Nervousness leads to rambling. Write down what you want to say and be sure to say it.

Concrete

Be specific about your symptoms. How long have you had a cough, felt a mass, noticed blood? What are your priorities and financial constraints? Are you willing to drive a longer distance, for example? Or do you live alone and therefore need to know if someone should stay with you. Before you leave, say out loud what next steps you need to take and your general understanding of the treatment plan. Request the contact information for a nurse, navigator or social worker that you can contact if you have questions after the appointment.

This scene from When Harry Met Sally illustrates clear, concise and concrete communication. Sally gets a bad rap, but no one questions what she wants and how she wants it although she has just sat down and barely reviewed the menu. How can you prepare to be this clear when speaking with your oncologist?

Correct

Accurate, truthful and credible. Have you read trusted sources before your appointment? You have 60 minutes with a highly skilled professional. Do you really want them to spend time debating a cure you saw on Instagram and didn’t take the time to investigate yourself? Do not bring totally new information into a physician appointment.

In this short skit from Scrubs, Carla and Turk spar over Carla’s ethnicity. It is important to her that he gets it right.

Coherent

Create a focused, chronological order of the events leading to this moment. How did you get here? By creating a comprehensive timeline, you may prevent the oncologist from having to dig around the electronic medical record for the answers. I suggest starting with “My symptoms started last XXX. I had my first scan XXX at XXX hospital.” and so on.

Complete

What key data is missing from your story? Does your doctor have all the information necessary to make a recommendation? What questions came up in your research or where did you find conflicting information? How does that apply to your specific situation? Create a checklist of questions ahead of time and ask the person accompanying you to the appointment to sure all the items are covered before the doctor leaves the room.

Courteous

Think about how to advocate for yourself without being rude. Indicate that you are looking for a partner and are willing to listen. You are not going to convince an oncologist that your approach to treatment is the best one. If you already know the right treatment, why are you there? It is also worth considering your goals for the consultation: to make a new friend or to find a competent physician who can treat your cancer. Doctors are humans too and come in all manner of personalities.

Even in the face of huge power differentials, it is possible for all of us to be coherent, complete and courteous.

Don’t show up to your doctor appointment empty handed or empty headed. Use the time between receiving a cancer diagnosis and your first appointment to learn about your diagnosis and possible next steps for treatment. Learning the basics will allow you to maximize the short time you have with your new doctor. Use the 7 C’s and all the information at your fingertips to prepare for an excellent communication experience. I can’t wait to hear how it goes!

“Think about how to advocate for yourself without being rude.” The first oncologist I went to - not 48 hours post diagnosis - was such a condescending asshole. I was absolutely stunned. How on earth could I trust this man when his bedside manner was beyond terrible? I refused to believe I had to accept his behavior - so I didn’t. The 2nd oncologist couldn’t even look at me. Again. How could I trust her? Her NP was much more open and forthcoming. I pressed the oncologist on why I needed certain treatments she was recommending. I wasn’t trying to be argumentative or a know it all - I was just curious (and of course that curiosity was probably driven by absolute fear of what I had to endure). She ended up taking my case to the tumor board and they stated that in fact I didn’t need that course of treatment she was proposing. I finally asked an acquaintance who had been through it who her doc was - and thankfully, I’ve been in his care ever since. He is an amazing partner in my healthcare - and I couldn’t be more grateful and trust him implicitly. It’s hard to manage the emotional distress of the decisions we have to make along with - what feels like - interviewing professionals that are tasked with saving our lives.

One of my patients always came with a post card with his questions and medication refills typed on it which was immensely helpful for us both.