A familiar face smiled at me as I turned from the podium and walked towards the edge of the stage. A line of audience members had formed at the bottom of the stairs, waiting to say hello or ask a question.

“It’s me, Donna,” she said as we embraced. Donna was a former patient I treated years ago. Through tears she told me how after her cancer treatment she lost her job and her home. “I finally declared bankruptcy and I’m sorry if you didn’t get all the money that I owed you.” My heart sank as she continued, “I just wanted you to know that I’m better now, my cancer is gone, and you were a great doctor.”

She hugged me again as I murmured words of support and she walked away. On my way home, I thought of how she struggled during treatment with the physical effects of her cancer and now of the financial burden that she hid so well during our weekly meetings.

As I scrolled through LinkedIn last week on International Day of the Woman, I saw a picture of a friend at the edge of a stage, and it reminded me of that conversation with Donna.

I always feel a bit conflicted on these women empowerment days. On the one hand, I love learning about barrier-breaking women – Elizabeth Blackwell, Sophia Jex-Blake, Rebecca Lee Crumpler and Anandabai Joshee, to name a few— who kicked open doors so that generations later, women like me could walk through.

I also enjoy seeing how others choose to celebrate (?) International Day of the Woman by highlighting men who’ve nurtured their dreams and supported their careers. Or by celebrating when people tag women friends and colleagues who help make life a little easier.

But it all just feels like a bit of a stretch to me.

Don’t get me wrong. I understand the importance of lifting up women heroes. I’ve also had incredible men knocking down barriers to create opportunities for me. And I rely daily on the love of my friends and family.

Setting aside just one day to acknowledge the experience of over half the world’s population, however, feels so…inadequate. Posts celebrating #girlpower seem performative when there is so much work to be done to lift women and so little time/attention/energy left to do it. Especially when it comes to cancer.

The Women, Power and Cancer report published last year in The Lancet unequivocally demonstrates the devastating impact of the current patriarchal approach to cancer on women around the world. In her introduction to the piece, NIH director Dr. Monica Bertagnolli commented that the report “presents a comprehensive, global view of how the unique difficulties that women face can limit their ability to overcome the challenges that cancer presents, both for themselves and for society overall.”

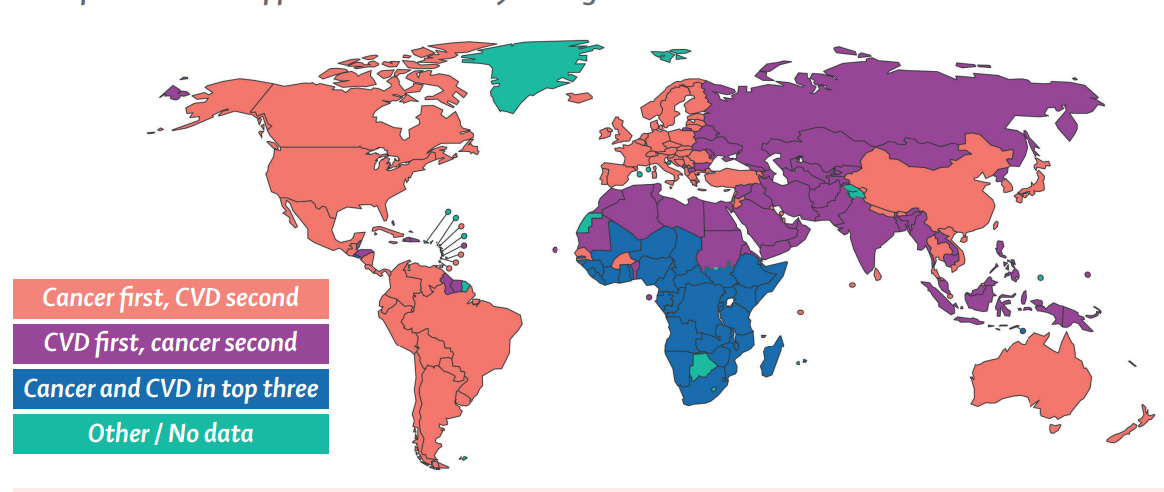

The report speaks candidly about gender inequities that lead to cancer being one of the top three causes of premature death among women in most countries. Sadly, almost all of the 2.3 million premature deaths be prevented with early detection, prevention, and access to optimal cancer care.

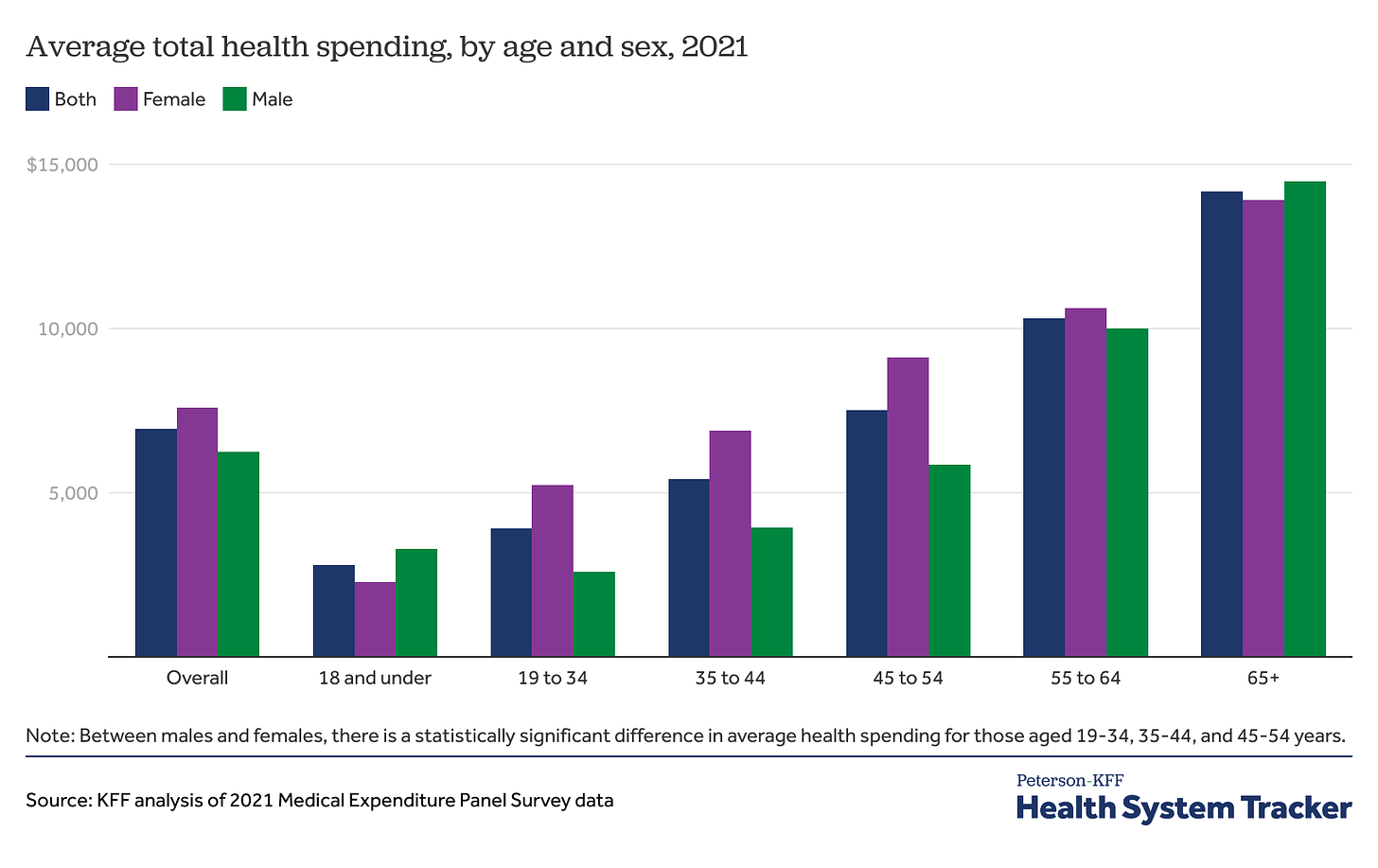

The report goes on to highlight the unequal financial burden faced by women because of cancer. In a PBS interview, Dr. Ophira Ginsburg, senior advisor at the National Cancer Institute's Center for Global Health and one of the co-authors of the study, said “We looked at women after one year of a diagnosis of cancer and found that three in four had suffered financial catastrophe…That doesn't even include the indirect costs such as transportation, childcare, the fact that women who are in the paid workforce have to leave those jobs in order to seek care.” This surprises no one who has watched a female colleague keep all the plates spinning while caring for a loved one or having cancer herself.

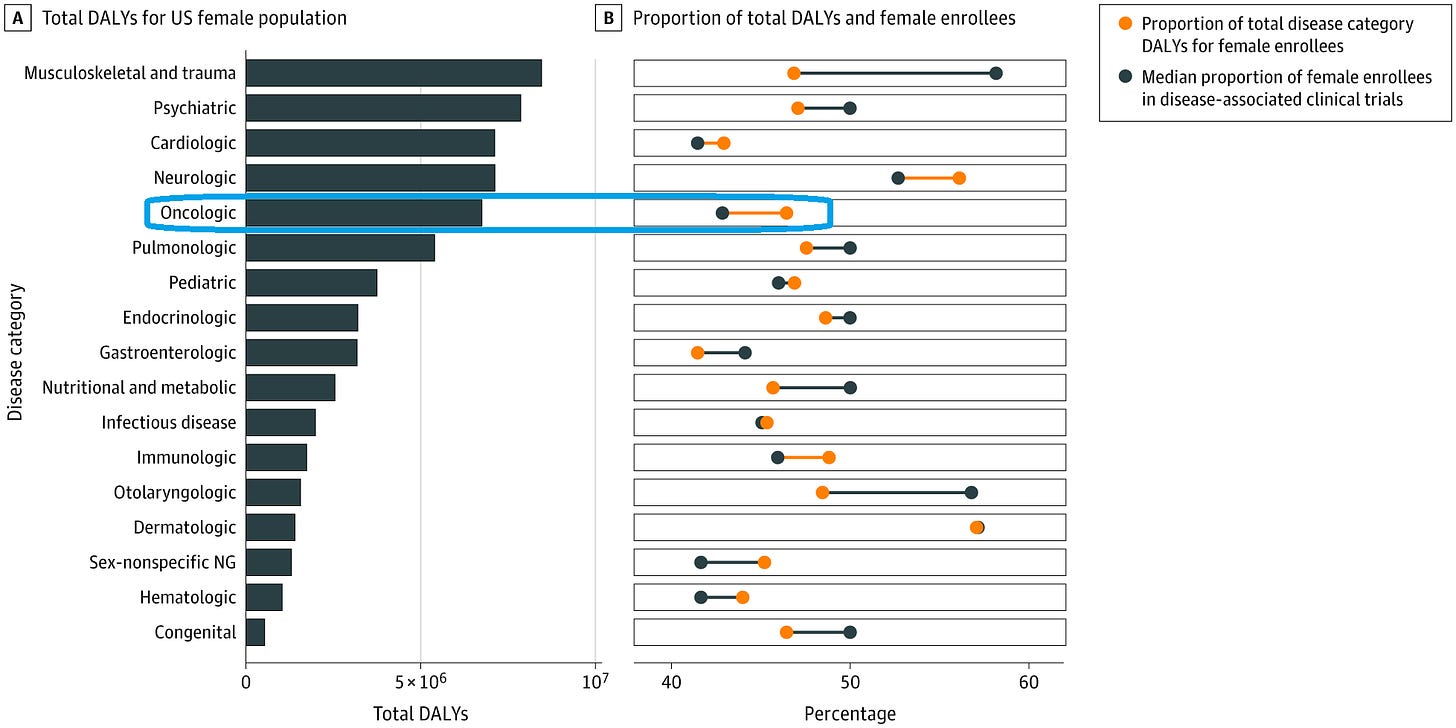

The report also highlights a lack of clinical research into important areas of cancer, specifically the impact on women of common cancer treatments and their outcomes. This lack of data on women not surprising.

Historically, women were not included in most clinical research trials (including those showing the effectiveness of common medications like insulin and penicillin) in order to ensure homogeneity in treatment effect and to reduce potential harm to a developing fetus. Positive study results in men were extrapolated to women.

The NIH began requiring federally funded researchers to include women in studies in 1993 and only then because of the insistence of Dr. Bernadine Healy, the first female director of the NIH. Dr. Healy conceived and implemented the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), a $500 million effort to study the causes, prevention, and cures of disease in women. It was through the WHI that we learned, for example, the differing presentations of chest pain in women.

Although the gender gap has closed in many areas of research, cancer still lags behind. A recent analysis of over 20,000 clinical studies in all medical fields found that cancer clinical trials had the lowest female representation.

It’s hard to find the cure cancer when half of those affected are not included in the studies looking for it.

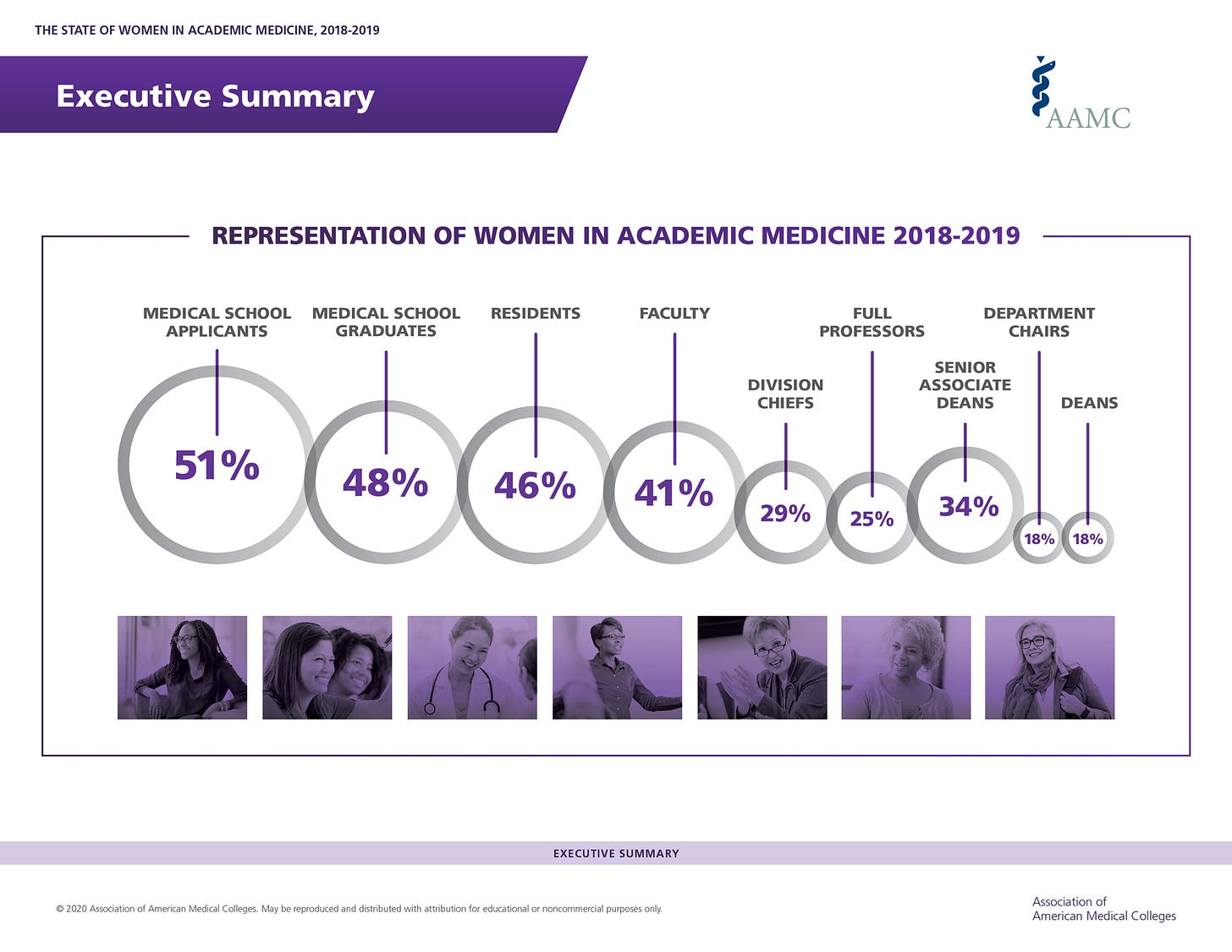

Another section of the Lancet report that caught my attention was a discussion of women in the oncology workforce. Here the authors note “many capable women are still held back from leadership opportunities due to long-held gender biases, workplace harassment, or lack of support or mentorship.” Of the 100 top cancer research journals, for example, only 16 percent had female editors in chief. Women are also more likely to receive smaller and fewer research grants.

This lack of representation ensures that women’s voices are not heard in the important rooms and publications where decisions regarding future directions in research and funding priorities are made.

The report outlines ten priority actions. These include public health strategies for addressing inequities experienced by women at risk or diagnosed with cancer. Intertwined with this (because that is every woman) is the acknowledgement that we must get more women into the rooms where decisions are being made. Addressing fears and misconceptions with population navigators as well as lowering the barriers to entry into health systems by shoring up public health infrastructure and providing screening services in communities will bring services to the women rather than waiting for them to get time off work, find childcare, and catch public transportation to come to us. I agree with these steps and offer a few more.

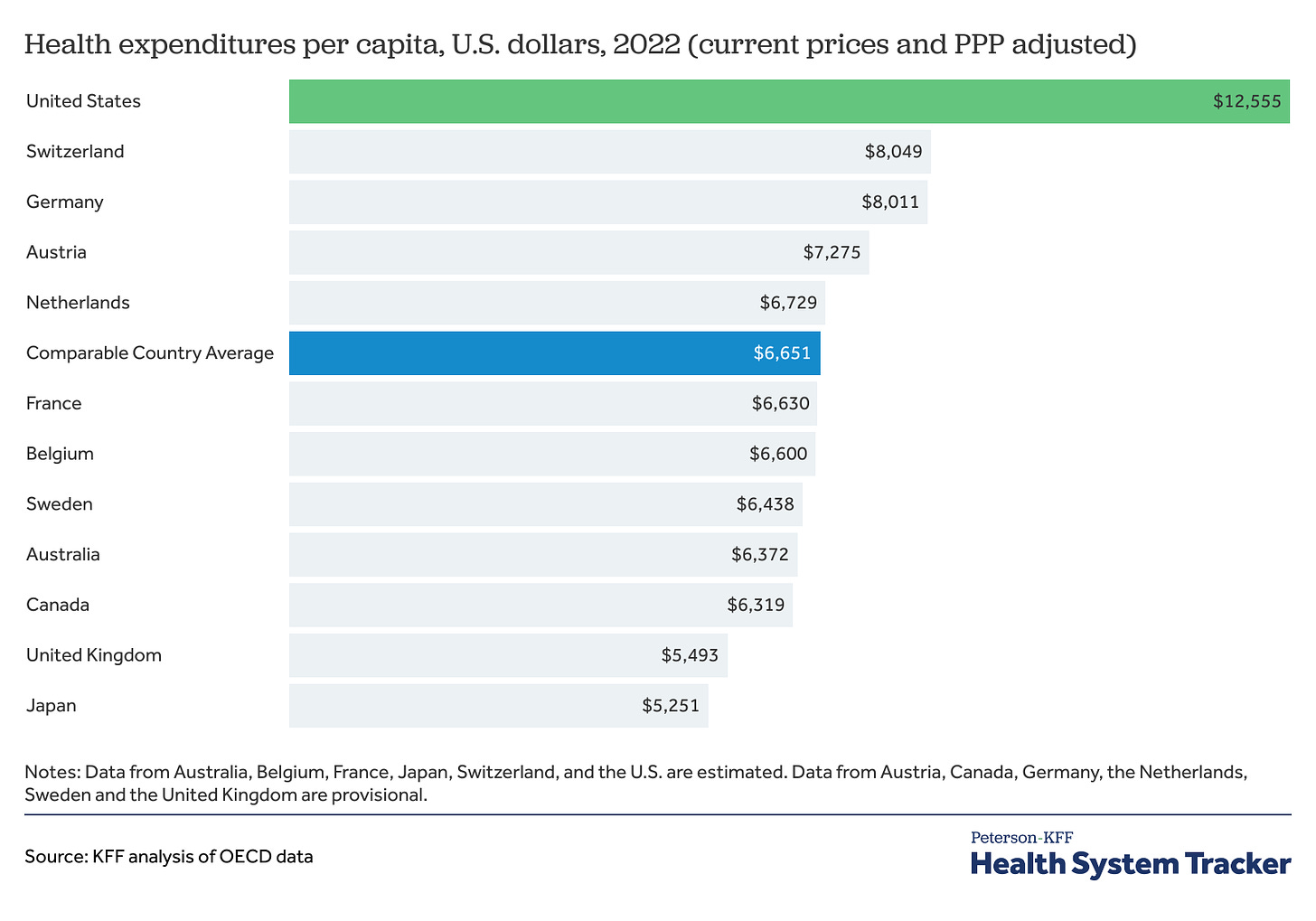

In the United States, we must acknowledge that our healthcare system is broken. Despite spending more per capita on cancer than any other country, cancer mortality in the United States is higher than six other countries that spend far less. The US spends on average $5 million dollars more per saved life relative to the closest four countries.

Our healthcare workforce is also broken. Four out of ten women leave full-time medicine within six years of completing their training. And for those who stay, women earn $2 million less revenue over a career as compared to their male counterparts.

To address these scary statistics, health systems can ask, “How can I help you stay in medicine and provide fair compensation for your contributions?” and make definitive plans to address those needs. From conversations at a recent meeting of women physicians, childcare, flexible work schedules and strong anti-bullying policies protecting female physicians would be good places to start.

We must also return to the professional collaboration between health specialties, each bringing their unique perspectives, rather than viewing each other as competition for limited resources.

And finally, we must incorporate gender equity education into every layer of the health care system. From elementary education to medical school, exposure to evidence-based health recommendations and the barriers that exist for women and girls to obtain those services must be emphasized.

It has been said that Ginger Rogers did everything Fred Astaire did backwards and wearing heels.

In the realm of cancer, women are barely on the dance floor. Through awareness and effort, I believe we can do better when we extend hands and ask women to join us on important stages and into groundbreaking studies. We can also create a new system that allows women to turn from unreimbursed care activities and pursue health literacy and financial independence.

For the next generation of women – our future patients and physicians—we have no other choice.

This drives me crazy. It is an issue that makes me furious and sad. And long before my cancer diagnosis. I am happy to see President Biden address it with his $12 billion initiative for women’s health—if it can get funded.

An avalanche of sobering statistics. Appreciate you putting this all together. A redundant sting seeing America spend leagues more as privatized healthcare is continually propped up to eat away at patients and providers alike— all while people, and clearly women especially, slip through the cracks.