Why Your Doctor is Leaving You

Decisions made behind the scenes may be affecting your care and your doctor can't always protect you.

In the rural area where I practice, two general surgeons recently retired, a medical oncologist moved out of the community and two urologists left over a year ago. My patients with cancer are left wondering who will care for them. And this small community is not alone. An aging physician population, burnout, and understaffing of other healthcare workers all contribute to rising rates of physicians moving and leaving communities.

One in five physicians say it is likely they will leave their current practice within two years. Meanwhile, about one in three doctors and other health professionals say they intend to reduce work hours in the next 12 months…The U.S. health care workforce is in peril. — Mayo Clinic Proceedings, December 2021.

Over the past 20 years, physician practice models have shifted. A majority of physicians, including me, are now employed by large health systems rather than owning their own practices. Although this may seem like a small thing, patients are often surprised to learn that the clinic staff do not report directly to the doctor but instead to a manager employed by the hospital. A doctor’s power to address even the smallest patient complaint may be limited and the responsibility of ensuring her orders are carried out falls to others. Most of the time this works well. The administrative burdens fall to skilled managers and the care team focuses on the patient.

This separation of powers if not well-executed, however, can lead to conflict regarding what is best for the patient. Physicians (and other health care workers) may find an uncomfortable gap between the plan of care they recommend with what other employees provide. Navigating this gap can be as simple as educating a staff member. Other times the physician is forced to accept substandard care delivery. Physicians must decide which decisions are worth taking to the mat and which they have to let go. Accepting this gap between what the physician thinks is best and what the staff provides can lead to moral injury. Although frequently used in a military context, moral injury is increasingly common in health care.

Health care is a team sport. When nurses and other support personnel are under tremendous strain or not able to perform at optimal levels, or when staffing is inadequate, the impact flows both upstream to physicians who then face a heavier workload and loss of efficiency, and downstream impacting patient care and treatment outcomes. — L. Casey Chosewood, MD, MPH, director of the NIOSH Office for Total Worker Health

I am grateful that we are past the days of surgeons throwing trays across operating rooms or sexually harassing nurses. This disruptive and dangerous behavior is unacceptable in any workplace. I am also deeply appreciative of the professionals and other vital personnel that support our patients. We should all work at the top of our license to care for the vulnerable humans who seek our help. Increasingly, institutions choose to prioritize consensus builders over mavericks when recruiting physicians. This approach, while admirable, ensures that only those towards the middle of the pack personality-wise will direct patient care. While employee satisfaction may be maintained, the patient may not always receive the best care. In the current environment with persistently high staff shortages, this is a difficult balance for health systems to make.

When we eliminate “difficult” physicians, however, we have to look at the cost. Will a patient die in the middle of the night while a group assembles to discuss how to address an arrhythmia? Or perhaps a neurosurgeon who risked it all to drill a bedside burr hole on a dying child was fired based on his personality rather than his skills?

I wish every physician could be all things to every patient AND every staff member. Sometimes when my patients come back to me after meeting a specialist, they confide “He didn’t talk very much” or “She was kind of rude.” I usually reply “You don’t need their personality. You need their hands, and they are the best.” Other times I have watched physicians with the highest patient satisfaction scores deliver awful care. Just like every other profession some people have it all, but most are flawed just like the rest of us. The question for the patient is “Does that flaw hurt or help the care of my cancer?”

From an institutional perspective, I get it. Mavericks are hard to manage. They are prone to disruption, pointing out difficult problems in the system, and refusing to capitulate to senseless regulations and ever-changing policies. Pleasant, consensus builders don’t end up in human resources or storm into C-suite offices demanding an incompetent staff member be fired immediately. Tied to practices by family, professional and moral responsibilities, most doctors try to accommodate and accept low level infarctions which mostly do not result in harm. In high-risk situations, however, someone has to make the final call and those orders must be followed. Medicine like many fields has begun the long work of addressing diversity and inclusions challenges. I would argue that different personalities are necessary to provide the breadth of patient care required by our increasingly complex human population.

Here’s an example:

After World War II, a civil war broke out in China. The Chinese Communist Party was eventually victorious leading to formation of the People’s Republic of China. For more than twenty years after the war, the United States limited trade and diplomatic relations with the newly established government and instead recognized the National party which fled to Taiwan. The civil war stranded many Chinese citizens in the United States including a young physician named Dr. Min Chiu Li ((李敏求).

M.C. Li was born in China and completed medical school at Mukden Medical College in modern day Shenyang. Leaving his wife and two young children in China, he traveled to the United States in 1947 to study at the University of Southern California. Stuck in America, he became a U.S. citizen and to avoid being drafted into the Vietnam War, traveled across the country to Washington D.C, joining the research laboratory as an assistant obstetrician assisting Dr. Roy Hertz at the National Cancer Institute.

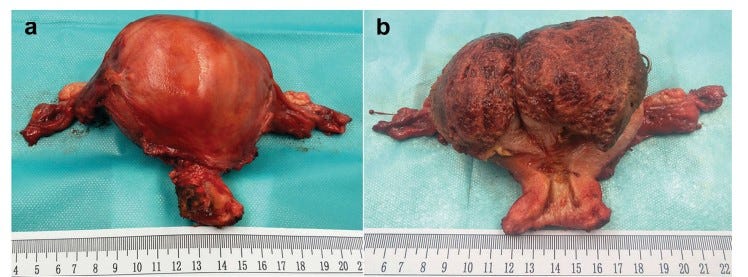

While at the NCI, Dr. Li observed young women dying of a rare cancer called choriocarcinoma. Choriocarcinoma forms in the uterus when cells that were part of the placenta begin to rapidly divide. This can occur with a normal pregnancy, miscarriage, or ectopic pregnancy. It is extremely rare, occurring in 7 out of 100K pregnancies, but in the 1950’s, it was uniformly fatal. Young women suffered through terrible pain and bleeding. Watching these young women die, Dr. Li became obsessed with finding a cure.

After studying the chemotherapy agent methotrexate, recently discovered by Dr. Sidney Farber and in routine use for the cure of childhood leukemias, he decided to start administering it to these otherwise terminal cases. He noticed that markers in the patient's urine dropped after she received methotrexate. He also realized that detectable levels of the markers in urine indicated that microscopic cancer was still present even if all visible cancer had disappeared and the patient’s health had improved. Because of the presence of these markers, he continued to give therapy for days after their symptoms had disappeared, an anathema in an age when the concept of microscopic disease was unheard of.

The first patient ever cured of choriocarcinoma was the 24-year-old wife of a US Navy dental technician who was near death after a tumor deposit of choriocarcinoma in her lung ruptured. Dr. Li went on to cure 2 other women before he was fired. Officials at a government agency specifically tasked with finding a cure for cancer fired Dr. Li in 1957 after he documented the first cure of a solid tumor using chemotherapy. Undaunted, he moved to New York where he joined the staff at Memorial Sloan Cancer Center and continued his research.

His insights that cancer was not cured if tumor markers remained elevated was a completely new way of thinking about cancer. Because he persevered after being fired, choriocarcinomas are cured today with chemotherapy as described by Dr. Li and his team. And yet a colleague described him as “pugnacious, very difficult, very hard guy, and we attributed [this] to his loneliness and his privations.” So, a new immigrant, unexpectedly separated from his family with barely passable English and little to no money cures a deadly cancer and they say he was kind of difficult? OK.

The recent Supreme Court decision has already placed undue burdens on schools trying to right the wrongs of standardized testing and institutional racism. Will medicine now be filled with perfectly vanilla personalities as well? How much care through compromise will patients tolerate?

Know someone affected by cancer? Share this newsletter with your family and friends.

On my mind…

I’ve been rewatching The Mindy Project. Hilarious with heart. And, like so many other shows, a wildly unrealistic portrayal of the life of a doctor. I’ve never left clinic in the middle of the day for the gym OR a fast trip to Staten Island.

I was sitting in a classroom learning about EKGs when the first plane hit the World Trade Center. Where were you on 9.11.01?

Highly recommend The Greatest Love Story Ever Told. One of the best YA books I’ve read since The Fault in Our Stars. You can download this self-published work for $3.49 on Amazon.

Great article and thanks for the historical reference.

I guess I’m what you describe as a Maverick. I advocate for doctors returning to practice ownership.

It's so nice to hear your perspective as an oncologist. I currently have leptomeningeal disease, a metastasis to my brain and spine and I'm outliving my prognosis. I've learned a lot about doctors personalities over the last 20 years since I was first diagnosed with bladder cancer. From a community clinic to a large cancer center, from neurosurgeons to small town urologists, from multiple surgeries, treatments, a clinical trial, remissions and progressions, I've learned to adapt to the doctor treating me. I found in the beginning a good bedside manner was paramount. Now, it's all about the science, experience and success rate of the doctor. I was reminded of this yesterday when a met a nephrologist to treat my solo kidney. He was all brain, no heart, but I trust him. I've had 2 oncologists in the last year leave clinical practice for research. I was sad to see them go but maybe they'll be like Dr. Li and find a cure for my type of cancer!