“What happens when they feel untethered? How will we keep them sane, especially with the 20-minute communication delay with Mission Control?”

Feeling disconnected from the “real” world is something patients undergoing cancer treatment frequently articulate so I was interested to read more.

The first step seems to be to find the “right” candidates for space travel. To prevent external mutiny and maintain internal unity among the Martian settlers, NASA is looking for people who possess “Goldilocks” personalities. They must “score neither too low nor too high on any of the “Big Five” personality traits—extroversion, agreeableness, openness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism,” writes Dowd. In NASA’s estimation, prospective Martians must be able to remain congenial to their colleagues/roommates AND overcome the extreme boredom which will accompany mundane tasks like scientific experiments and space station maintenance. I have a few thoughts on this:

Wait, what? You’re on Mars and you’re bored?

If those are the personality criteria, Elon Musk is never going to Mars.

After enduring the gauntlet of cancer treatment, survivors and their caregivers would make great Martians.

Wait, what? You’re on Mars and you’re bored?

To screen for boredom tolerance, the Japanese equivalent of NASA asked astronauts to fold 1,000 paper cranes and observed whether there was deterioration of the work over time. Dowd quips “I feel sympathy for those who have failed to achieve their childhood dream due to a sloppily folded piece of rice paper.” I mentioned this task to a patient who replied drily, “Folding paper cranes? Try answering the same 87 questions about your bowel movements every week for a year.” Touché.

Reading about boredom among Martians, reminded me of what I learned during a college internship at Biosphere2.

It turns out the original Biosphere2 inhabitants rapidly abandoned routine maintenance and science experiments because they were forced to spend 16 hours a day cultivating food. The project was called off after only a few months because the subjects were literally starving to death. (Matt Damon also spent much of his time in The Martian spreading…erm…fertilizer on potato plants and didn’t ever complain about being bored.)

Given these experiences, I’m not sure we should worry so much about Martian boredom. A bunch of Type A people in a stressful situation with little to no outside contact killing each other? Sure, but boredom? I don’t know.

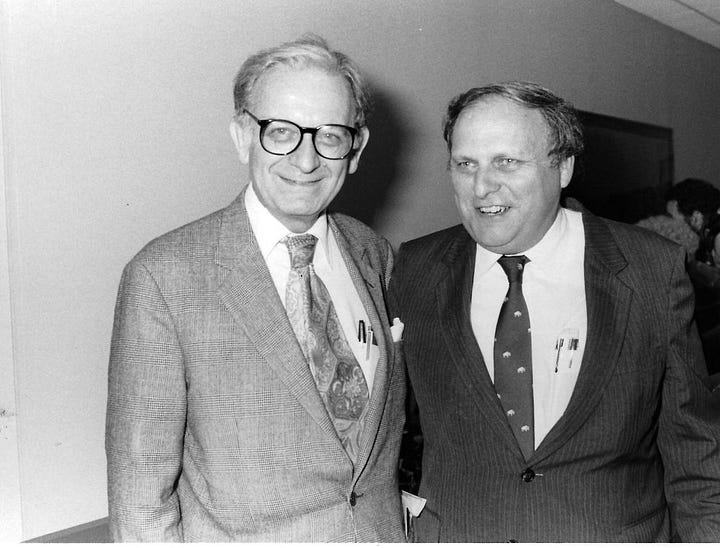

After almost two decades in oncology, I’ve heard patients express almost every feeling imaginable as they pass through our strange world, but never boredom. I’ve also never heard it from cancer researchers. In fact, this concern with boredom and inability to focus is in stark contrast to the attitude of physicians at the frontier of oncology in the 1960’s. Dr. Jerome Yates, the groundbreaking researcher who developed the first successful treatment for acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), describes other physicians’ perception of their work this way: “The attitude among our physician colleagues was, why are you wasting your time doing this? Not only are you wasting your time, but you’re making the patients sicker.”

“[They said] we were poison pushers… we were cowboys…we were doing things that weren’t in the best interest of the patient.”

The “father” of chemotherapy Dr. Jay Freireich often joked that he’d been fired from every hospital he worked at for having the audacity to believe that curing cancer was possible. Obviously, they weren’t on Mars, but according to other doctors, they might as well have been.

Enduring this intense criticism and watching the agonizing deaths of most patients they treated, early oncologists like Yates still pressed forward. They didn’t complain of boredom and certainly didn’t meet any standards of the “perfect” psychological profile. In fact, quite the contrary. As Dr. Yates recalls, “I mean, we were like the Rodney Dangerfield’s of medicine in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s.”

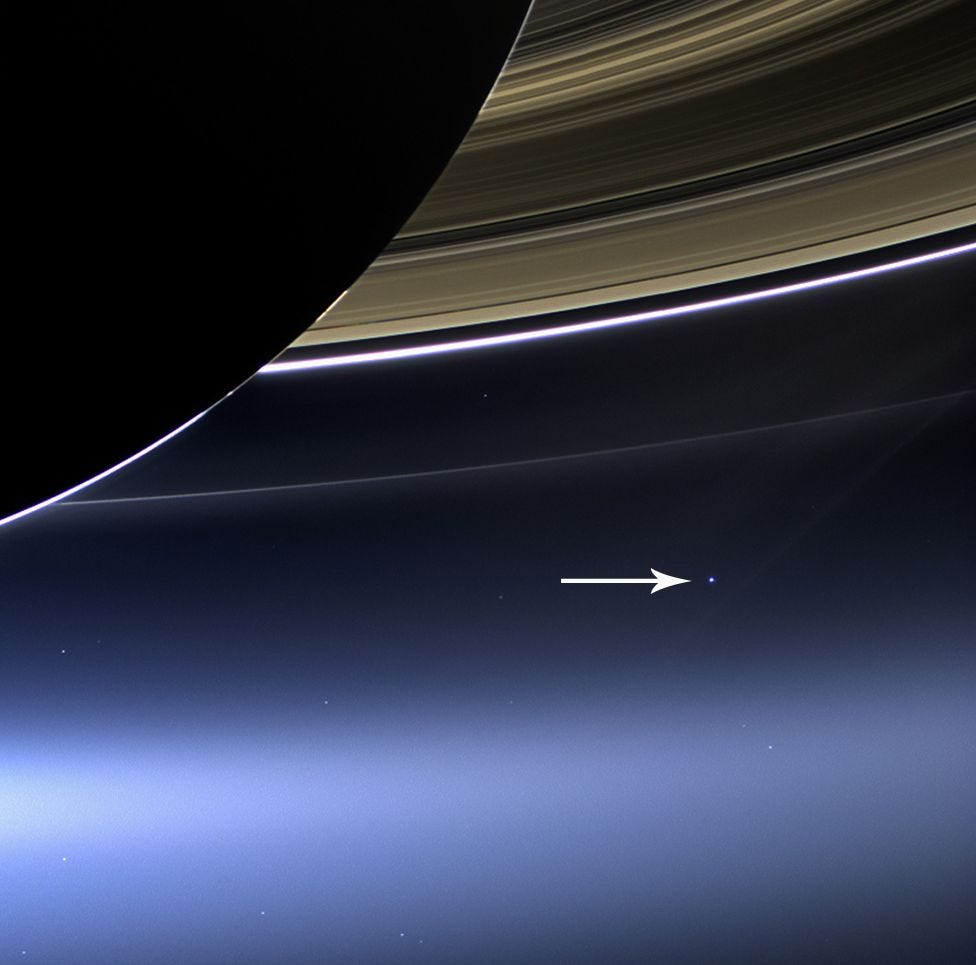

As someone whose childhood idols were Jacques Cousteau and Jean-Luc Picard, I get the draw of “exploring strange new worlds to go where no (wo)man has gone before.” But we also can’t get bored with cancer. We can’t get bored with the suffering, death and impact of this familiar plague and run off to sexier pursuits.

The good news is that WE CAN DO THIS! Over the past fifty years, we have made tremendous strides in curing cancer. I have immense appreciation for the researchers who have dedicated their careers to finding better, safer and earlier cancer detection methods and treatments. BUT we also need to attract the renegades, those crazy dreamers who crave the adrenaline rush of impossible missions and as a result, push us into as yet unimagined futures. We need more Rodney Dangerfield’s. Let Goldilocks go to Mars.

On my mind…

I recently devoured Between Two Kingdoms,

‘s gripping memoir of her leukemia treatment and life afterwards. As the director of our survivorship program, sentences like this haunt me: There is no restitution for people like us, no return to days when our bodies were unscathed, our innocence intact. Recovery isn’t a gentle self-care spree that restores you to a pre-illness state. Though the word may suggest otherwise, recovery is not about salvaging the old at all…it is an act of brute, terrifying discovery.Wildfire is for women “too young” for breast cancer. Each issue is filled with gorgeous work created by Stage I-IV breast cancer patients.

Why does Neil Armstrong think space exploration stopped after landing on the moon: “We lost the public will to continue.”

Thank You for Being a Friend:

Listen to a cancer cell die. Courtesy of themostbeautifulsound.org