Hi everyone! My podcast, Less Radical, has been nominated for TWO Webby Awards. I would love to use this international stage to highlight the impact of NIH funded researchers like Dr. Fisher. So, if you haven’t had a chance, please take a minute before reading and vote for us by clicking here and here. Voting closes April 17th. I really appreciate your support!

Last week, Emily Henry’s Beach Read finally arrived on my Libby app. Craving a simplistic romantic trope and a predictably happy ending after a winter of heavy non-fiction, I immediately downloaded the audiobook when it became available.

Released in the summer of 2020, Beach Read is an enemies-to-lovers story of two writers struggling to overcome writer’s block while living next door to each other in a quaint vacation town on the shores of Lake Michigan. The cover evoked a misunderstanding over an ice cream cone and, at most, a bicycle accident leading to a clumsy first kiss.

The opening of the book finds the main character, January Andrews, processing her father’s sudden death and the revelation (at his funeral!) of a years-long affair with his childhood sweetheart. The story moved fast and had me hooked. I was floating right along until Henry reveals that January’s mother had recently completed treatments for cancer. I sighed but kept reading.

I kept reading while overlooking the incredible twist of fate that resulted in college classmates (and well-known authors) living next to each other in an obscure Midwestern vacation retreat. (This is a rom com!)

I even stayed with Henry as she described two people having sex in a tent next to the burned down remains of a suicide cult during a thunderstorm. And as she casually implied childhood abuse including a father breaking the arm of a child.

Henry lost me when she revealed that January’s father reignited his affair after learning that his wife’s cancer had returned.

In a letter that January reads after her father’s death, he expresses regret for the time he spent away from her and her mother, provides an explanation for his behavior, and attempts to justify seeking comfort in a healthier woman’s arms. He can’t face her disappointment, but feels it is important for her to “someday” read these letters in order to know him completely. January’s mother, the two-time cancer survivor, refuses to discuss the issue with her adult daughter.

Working with editors on my own book, I can hear their feedback on these pages. “You’ve got to raise the stakes. An affair is not enough. How can you make it MEAN something bigger?” Henry, I suspect, obligingly reached for one of the biggest stakes known to humans - cancer.

“Both characters go through a lot of emotional ups and downs.”

“All the characters were fun.”

“I loved everything about Beach Read.”

“It is about finding inspiration in unexpected places.”

I have lived enough of life to understand that people are complicated and make decisions that hurt others. I have also cared for women whose partners have left them during cancer treatment.

I remember April whose husband left her and three young children because he “couldn’t handle” her cancer diagnosis. When he reappeared, holding her hand, at a follow-up appointment a year later, I could barely hide my disgust as I recalled how April sobbed as I hugged her during our weekly appointments and how our staff entertained her young children while she received her treatments every day.

A tarnished sliver bracelet rests on the corner of a picture frame on my desk. It is a gift from Amy whose abusive husband beat her during treatment and then filed for divorce when she developed brain metastases. Lawyer’s bills piled up as her hair fell out. Her mother stopped by my clinic after Amy died, pressing the bracelet into my hands while tears spilled from her eyes. She was trying to gain custody of Amy’s children who she suspected were now subject to her former son-in-law’s rage.

While January supports her mother through treatment and strives to create the perfect life her mom envisions for her, the man in their lives buys a lake house to escape the messiness. After his death, forgiveness is apparently the only path available to January - his betrayal brushed away as she (too quickly IMHO) accepts his human fallibilities.

Yes, I understand this is a rom com, but this is also how the culture around cancer is created and norms of behavior reinforced. Henry made a choice to base infidelity around cancer recurrence thereby setting up a permission structure that those who have “failed” to stay healthy are worthy of abandonment. Or at least should understand if those around them leave. And then must welcome them back when/if they decide to return. Cancer, the patient must accept, is an individual experience.

In contrast, I read

recent essay “What Sustains Me in a Time of Political Cancer.” She writes:Like this second Trump administration, my second diagnosis was much more destabilizing. I no longer had the assurance that I would survive. This thing was really out to get me, it seemed. I had to learn how to live with the reality that a stray cancer cell could be lurking in my body, silently growing, waiting for its opportunity to strike again, perhaps fatally.

She outlines how she narrowed her priorities and with the support of her husband and son focused on what got her through one day at a time.

Both at work and at home, I had to learn to be okay with letting other people take care of things. No, the house wasn’t going to be clean the way that I wanted it to be. And meals? Yeah, throw nutrition out the window. With one set of chemo drugs, I could only tolerate starchy foods. I practically lived off baked potatoes, blueberry muffins, applesauce, and rice noodle soup. And I decided that the best option for my parenting stress was to stay out of my husband and son’s decisions about what they were going to eat. Sitting upstairs in my recliner as they carried on life downstairs, I learned that they could manage without my over involvement.

When I started Beach Read, the Andrew Wyeth exhibit that Todd and I went to see on Valentine’s Day was still fresh in my mind. I have long been a Wyeth fan, drawn to his portrayal of disability and desire in Christina’s World.

“One of the most popular and celebrated American artists of the twentieth century, Andrew Wyeth spent seven decades painting a particular farm in his hometown of Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania…This exhibition tells the story of the connection between artist and place—one of the most enduring connections in American art.”

A seven-decade observation of one family covers a lot of ground, including the death of the family matriarch, Karl Kuerner, from leukemia in 1978.

At first depicted as the strapping, young head of household, Wyeth dares us to ascribe any weakness to Kuerner, a German war veteran turned farmer. Wyeth’s depiction of Kuerner’s slow death from cancer, however, shows a very different man.

The curator’s note next to the painting below read “Karl Kuerner was diagnosed with leukemia in 1970, and his illness lingered for years. Often, he lay on a bed on the first floor of the house where Wyeth began to sketch him. This once virile man, who had always been represented as emphatically vertical, was now supine and weakened. Despite the starkness of the image, Wyeth conveys great sympathy for his friend and neighbor.”

Wyeth combined his sketches into a final piece he titled Spring.

Through Wyeth’s magical realism, we see his friend slipping away, earth to earth, dust to dust. Wyeth said, “I felt he was going back into the hill he loved so.”

Wyeth’s careful consideration of Kuerner’s body and his placement in the field demonstrate the artist’s warm feelings towards his longtime neighbor and friend. The stark landscape and dark tones convey Wyeth’s sadness and sense of loss.

In this exhibit, we do not see the process of cancer unfold, only a moment in time near the end. Kuerner is silent. Our last glimpse of him is in a corpse-like fugue.

Was that how Kuerner felt or was this Wyeth processing his own mortality through the slow death of another human?

When I was in the hospital for the transplant and my brain became fuzzy with chemo, my journal was a constant companion. I recorded conversations with doctors, symptoms, treatments, side effects, frustrations, and how I felt about it all…

This newsletter will be about my experience and how it’s changed me in unexpected ways. My hope is by sharing my story other people struggling with life-threatening diseases and the arduous treatments won’t feel so alone.

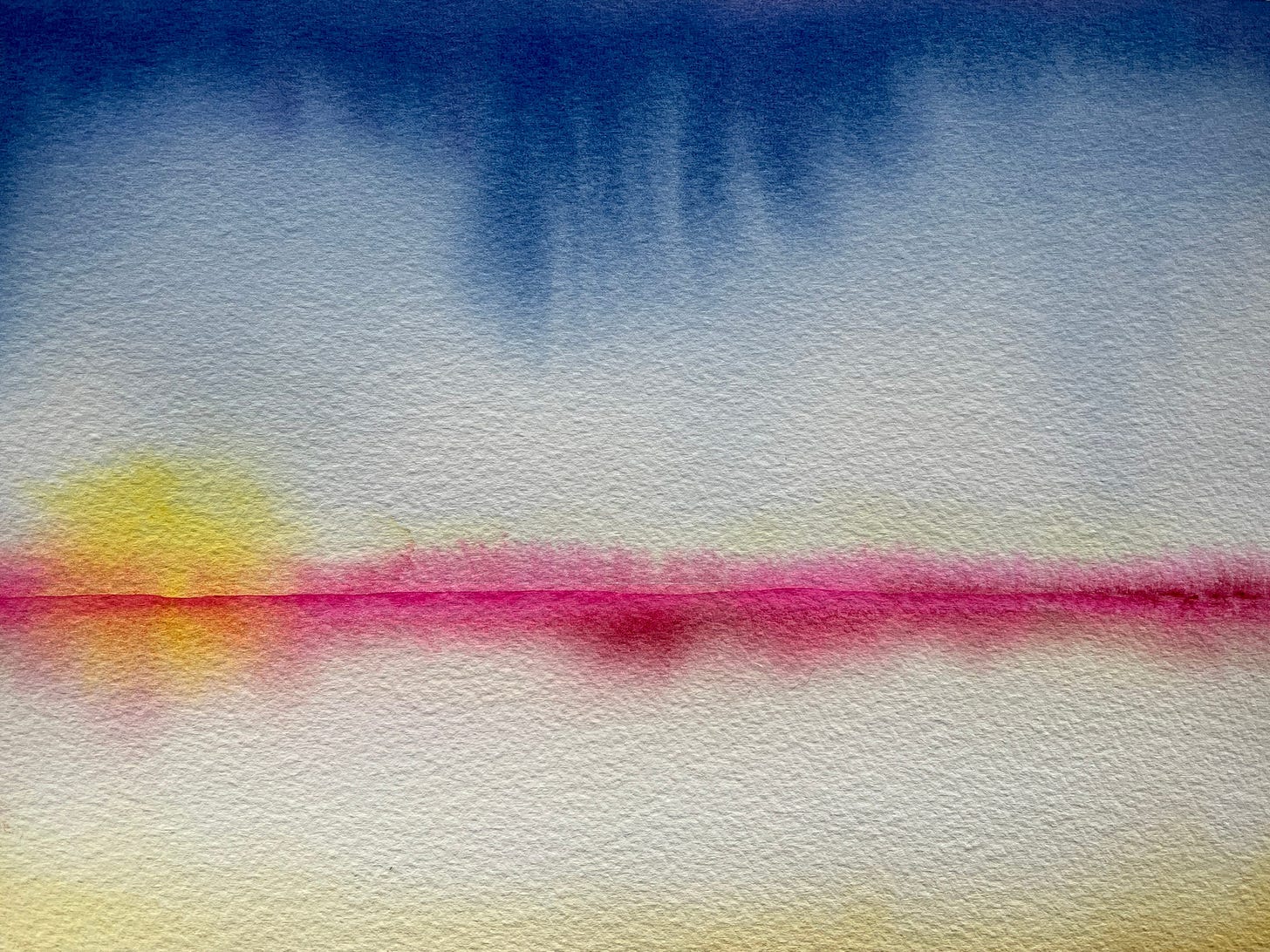

She recently shared this watercolor along with a poem:

There is a calm I feel each time I pick up a paintbrush. Colors blend and transform. Shapes develop. Light emerges. There is a calm I feel when I escape into a book. I stop thinking about politics, and cancer, and transplants. There is a calm I feel kissing my grandson’s head. It smells like bananas, or freshly mown grass, or wet pennies. There is a calm I feel in the silence of my very small world. Here I can let go of fear, and anger, and unresolved conflicts. This calm empowers me to allow each day to unfold as it will. Whether I like it or not.

Artists and writers invite us to consider cancer - as we scan past it on the pages of a book or stroll past it on the wall of a museum. Henry and Wyeth process it at arm’s length while Richards and Walker-Barnes ground the experience into our present experience.

Which is the true experience of cancer?

In his memoir All the Beauty in the World, Patrick Bringley details his decade long career as a security guard at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He takes the job as he seeks to escape from the grief of his brother’s death from metastatic soft tissue sarcoma.

Bringley reflects on a 14th century painting depicting Christ’s crucifixion:

The body of Christ is limp, but dignified, a gentle elegance in his bearing suggests that he suffered bravely. Mary and John sit reflectively on the ground. They look tired above all; the frenzy of the day has passed and only the death remains.

The blunt fact. The impenetrable mystery. The immense and immovable finality…

Daddi has painted suffering; it seems to me. His picture is about suffering. It has nothing on its mind except suffering. We must look on it to feel the great silencing weight of suffering or we don’t see the picture at all.

Much of the greatest art, I find, seeks to remind us of the obvious. “This is real” is all it says.

Each of us creates with a different purpose: to process, to educate, to entertain, to persuade, or to make a living. Before using cancer to accomplish this goal, however, we must pause and consider whether we are the ones who should be telling that story.

Wonderful read. Thank you. Tom Lake might be a good antidote to the failed summer rom-com. ☺️

Thank you for sharing my work. I appreciate you writing about the reality of cancer. Your patients are lucky to have you.

And, congratulations on your nomination. I'm adding your podcast to my list!