First, thank you all for your kind words about last week’s post. Perhaps I can get Todd back for another round sometime. It was fun to hear from all of you.

So Happy President’s Day! Relatively few of our leaders have publicly disclosed cancer diagnoses, but there are a few. Going back over a hundred years, Ulysses S. Grant died of larynx cancer; Grover Cleveland had a tumor removed from the top of his mouth on a yacht and Lyndon Johnson had a skin cancer removed in 1967. Some have hypothesized that President Eisenhower had a rare adrenal tumor called a pheochromocytoma that contributed to his difficult to control high blood pressure.

In my lifetime, President Reagan had part of his colon removed when a cancerous polyp was discovered as the cause of his anemia and Jimmy Carter is almost a decade into his Stage IV melanoma diagnosis. Recently, President Biden had a basal cell carcinoma removed from his chest and King Charles is undergoing treatment for an incidentally found prostate cancer.

If you want to read more, you can check out my previous posts covering the impact of First Ladies Betty Ford and Nancy Reagan’s cancer diagnoses by clicking the links below.

This week I’ll be diving into the story of how cancer impacted the life of my second favorite president who happens to be our second president, John Adams. (As a Central Illinois native, obviously Abraham Lincoln takes my top spot.)

Thanks again for reading and please invite a friend to join the conversation!

John Adams had only one daughter, Abigail, or “Nabby” as her family called her. While her father was serving as America’s first ambassador to England, young Nabby fell in love with her father’s secretary, William Stephens Smith. Nabby’s mother, Abigail, had significant reservations about the young man calling him “wholly devoid of judgement.” Despite this, the couple married after a quick courtship and returned to the United States.

Back in the US and with several children now in tow, Smith made and lost several fortunes. One dubious transaction in which he was accused of shipping supplies from New York harbor to support the Venezuelan Revolution in 1806 landed him in court. Found not guilty, but stripped of his titles and remaining wealth, Smith eventually settled on a farm in western New York with Nabby and his four children. Far from the intellectual and social stimulation of her parents’ home in Quincy, Massachusetts, Nabby capably ran a large, frontier homestead while living in relative poverty.

Sometime in 1810, Nabby felt a mass in her left breast. Barriers familiar to rural patients of today—scarcity of trained medical professionals, poverty, and her own denial—prevented her from seeking treatment at first. Despite applying salves to her breast and taking oral hemlock supplements as recommended by a local practitioner, the mass continued to grow, eventually becoming “harder with a little pink at times on the skin.”

Nabby wrote to her mother, Abigail, in February 1811 that she feared the mass was cancer. Upon receiving her daughter’s letter, Abigail consulted physicians in Boston, who concurred with the prescribed hemlock treatment. As her daughter’s breast pain increased, however, Abigail began lobbying for her immediate return to Quincy, a grueling six-day journey.

Nabby finally arrived in June 1811 and immediately consulted several local physicians. All again agreed that observation was best, reserving surgery only if the mass became “enflamed.” Satisfied and desperately wanting to avoid a frightening surgery, Nabby prepared to return to New York. Before she left, however, she wrote one last letter to an old family friend - physician and Declaration of Independence signatory, Dr. Benjamin Rush.

Dr. Rush replied to her letter through her father:

After the experience of more than 50 years in cases similar to hers, I must protest agst: all local applications, and internal medicines for her relief. They now and then cure, but in 19 Cases Out of 20 in tumors in the breast, they do harm, or suspend the disease Until it passes beyond that time in which the only radical remedy is ineffectual. This remedy is the knife. From her account of the Moving state of the tumor it is now in a proper Situation for the Operation. Should She wait ’till it suppurates, or even inflames much, it may be too late. The pain of the Operation is much less than her fears represent it to be.

The recommendation of a trusted family friend carried great weight, and Nabby consented to surgery.

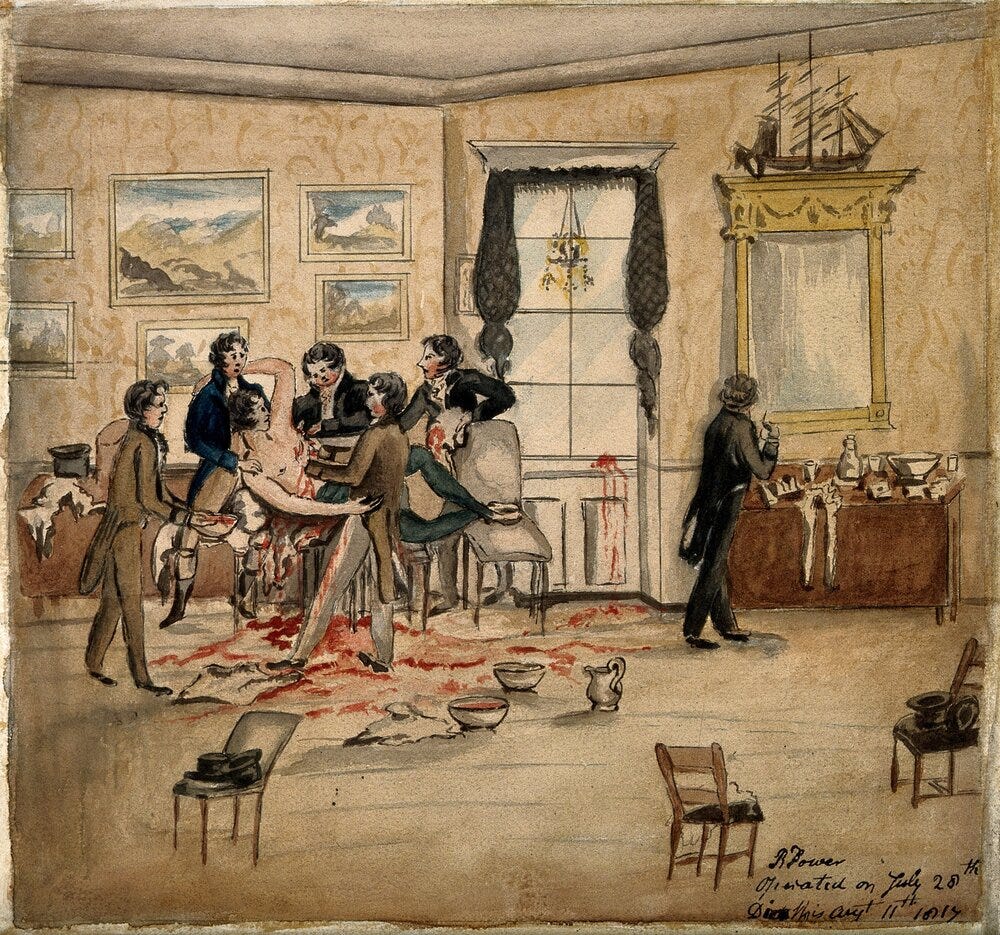

The operation took place on October 9, 1811, in her parents’ home with her family present providing support. A team of Boston’s most preeminent surgeons arrived a day early and explained to Nabby and her family the horrifying procedure. The surgeon offered no alternatives. Historian James Olson recreated the scene in his book, Bathsheba’s Breast, based on the few published contemporaneous reports.

After slipping off her sleeve to expose her breast, male assistants dressed in frockcoats, belted Nabby’s waist and legs to a chair. Her family restrained her shoulders and neck while the surgeon moved into place:

[He] then straddled Nabby's knees, leaned over her semi-reclined body, and went to work. He took the two-pronged fork and thrust it deep into the breast. With his left hand, he held onto the fork and raised up on it, lifting the breast from the chest wall. He reached over for the large razor and started slicing into the base of the breast, moving from the middle of her chest toward her left side. When the breast was completely severed, [he] lifted it away from Nabby's chest with the fork...Nabby grimaced and groaned, flinching, and twisting in the chair, with blood staining her dress and [his] shirt and pants. [He] pulled a red-hot spatula from the oven and applied it several times to the wound, cauterizing the worst bleeding points. With each touch, steamy wisps of smoke hissed into the air and filled the room with the distinct smell of burning flesh. [He] then sutured the wounds, bandaged them, stepped back from Nabby, and mercifully told her that it was over.

The operation took less than 30 minutes, but her mother and sister-in-law spent an hour dressing her wounds. Since the use of anesthesia during surgery had not been discovered yet, I’m not sure what surgery Dr. Rush was referring to when he assured John and Abigail Adams “The pain of the operation is much less than her fears represent it to be.”

John Adams updated Dr. Rush a few days after the surgery:

The Surgeons all agree that in no Instance did they ever witness a Patient of more Intrepidity than she exhibited through the whole Transaction. They all affirm that the morbid substance is totally eradicated and nothing left but Flesh perfectly sound. They all Agree that the Probability of compleatt and ultimate success is as great as in any Instance that has fallen under their Experience.

Nabby stayed with her parents for the rest of the winter to recover and regain her strength.

By the spring of 1812, more than six months after her surgery, Nabby returned to New York. By the end of 1812, however, she wrote to her mother complaining of bone pain and headaches. Nodules eventually appeared along the mastectomy scar, and it was clear that her cancer was back, and she would not survive.

Determined to die with her family in Quincy, Nabby convinced her husband to bring her home, enduring unimaginable pain as the carriage bumped and crashed back over three hundred miles of primitive dirt roads. When she finally arrived, Abigail was reportedly so shocked at her daughter’s emaciated appearance that she took to bed, leaving her father and sisters-in-law to care for her.

Nabby Adams Smith died on August 9, 1813, less than two years after her initial, brutal surgery. John Adams wrote to his friend Thomas Jefferson:

Your Friend, my only Daughter, expired, Yesterday Morning in the Arms of Her Husband her Son, her daughter, her Father and Mother, her Husbands two Sisters and two of her Nieces, in the 49th. Year of Age, 46 of which She was the healthiest and firmest of Us all.

The two Presidents had been estranged for years and Nabby’s death helped heal old wounds. Adams and Jefferson both died on July 4, 1826, the fiftieth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Not knowing that his friend had died earlier that day, Adams’ last words were reported in the local papers: “Jefferson survives.”

Stories of breast cancer treatment and (mostly) failures in women of privilege form a long pink ribbon through history. We can only imagine the horror of treatment in those whose voices are not recorded. As we now know, by the time Nabby was strapped to a chair, breast cancer cells were present in the rest of her body. Perhaps had she presented in 1810, when she first discovered the lump in her breast, the surgery, still incredibly brutal, may have cured her.

Instead, like so many women saddled with household responsibilities, she followed the advice available to her, using topical salves and natural treatments for years before seeking the care of a physician. And like so many women before and after her, trepidation surrounding the brutality of cancer treatment also likely led to denial, until the cancer finally asserted itself as a problem that could no longer be ignored.

She also did what so many of my patients do - reach out for help from friends, family and acquaintances. Nabby’s brutal surgery in her parent’s home aside, her experience is not so different from today. My phone or email pings with a friend/family member/friend of friend who has been diagnosed with cancer - what should he/she/they do? Where is the best place to go? Does this sound right?

We are connected to each other through the unexpected and unwelcome announcement of random events like cancer. And when someone, reaches out for help, we show up. Although none of us have a signer of the Declaration of Independence on speed dial, a friend with a kind word and a hug is plenty.

I urge you to connect with a cancer survivor in your circle. Or better yet, a caregiver supporting someone with cancer. A kind text, a handwritten note, a warm response on social media is all that is required.

Great read and I can't emphasize the last paragraph enough.

Really enjoyed this journey into history, and really well written. And so tragic. What a reminder how our past informs our present.