The Patient I Didn't Treat

A story about starting college and finding friends in unexpected places

Hello everyone. Before jumping in, I wanted to acknowledge the news that President Joe Biden has been diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer. Of course, my thoughts are with him and his family as they navigate through this time of uncertainty. Cancer is difficult and to manage it while the world watches/judges must add additional stress.

When a public figure shares this news, I find it can also be triggering for survivors living with, through, and after their own diagnoses. Well-meaning friends may forward articles, wondering if you received the same treatment. Or perhaps the presence of oncologists on television and a barrage of social media posts highlighting a celebrity’s cancer can make it feel like “cancer is everywhere” as one patient remarked to me today.

Before starting Cancer Culture, I was a contributor for Psychology Today. My writing focused on topics relevant to cancer survivors. In January 2023, I wrote an article about what happens when a celebrity announces a cancer diagnosis:

For survivors, cancer in the news can trigger memories of their own cancer treatment, renewed fears of recurrence, or questioning if their cancer treatment was correct.

First, this is normal. In our celebrity-focused culture, we are bombarded with advice from celebrities—from face creams to credit cards. And companies wouldn’t pay these spokespeople millions of dollars if their messages were not getting through. Our brains, therefore, are accustomed to listening to what a celebrity is doing. This may be fine for a decision about which car to buy or which travel website to use to book a vacation, but when it comes to cancer treatments, consume with caution.

You can read the rest of the article here. It includes some strategies to combat doomscrolling if you find yourself drawn to that this week.

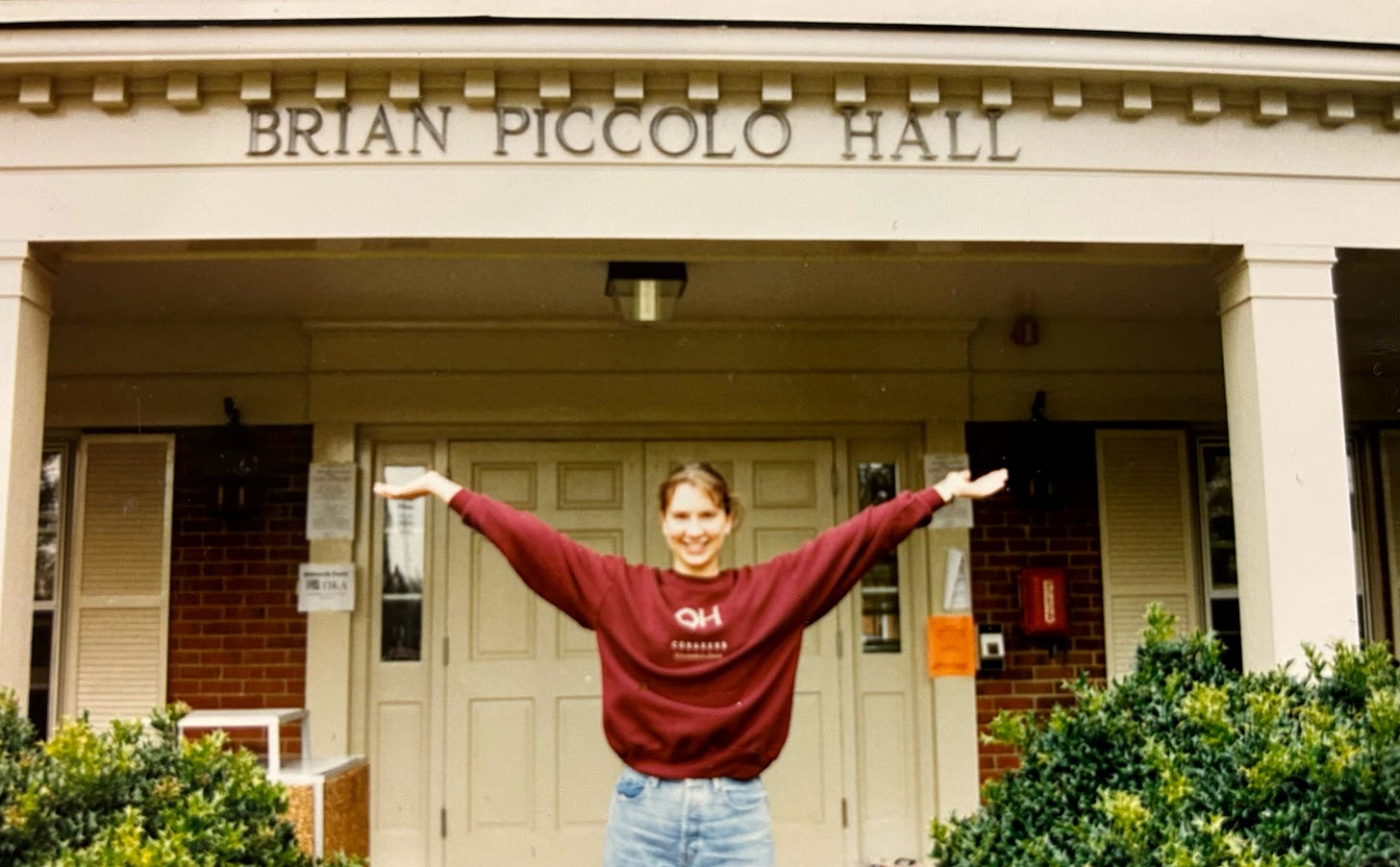

The summer before my freshman year I received my dorm room assignment in the mail. I was assigned to Brian Piccolo Hall. Located at the northeastern-most side of campus, the single-story building (and its twin Arnold Palmer Hall) had been built to accommodate athletes. The buildings featured oversized rooms with extra-long twin beds and cavernous showers. These deluxe amenities ALMOST made up for my dorm’s location on the opposite side of campus from the science buildings where my 8AM classes were held.

New NCAA regulations, however, prohibited segregated housing for athletes. So, when I showed up in the late summer of 1996, a golfer, tennis player, track star and several football players were mixed in with the rest of us normies.

My first college boyfriend was a 6’10'‘ offensive lineman who lived in Palmer. Despite his busy practice schedules and my crushing pre-med course load, we hung out often and I got to know his teammates well. (Anyone who says college sports offer a “free” education has not experienced the grueling expectations placed on Division I athletes.) We eventually broke up and lost touch after graduation.

Years later, I returned to Wake Forest to complete my radiation oncology residency. Winston-Salem felt like home, a sensation that was reinforced when I found my freshman year RA in Piccolo sitting at a desk next to mine in the residents’ office. What a small world, I thought.

As residents, we were assigned to disease-specific services for three-month rotations. I started on the brain tumor service. It was difficult, but I had a great teacher and the patients were wonderful. On one afternoon, I flipped through a chart (We still had paper charts!!) outside a patient’s room, preparing to take a history and report back to my attending physician. The name seemed vaguely familiar. I opened the door and caught my breath.

Sitting on the exam room table with a half-shaved head and a garish craniotomy scar was an old acquaintance. I sat down on the rolling stool and tried to collect myself. He got up and gave me a hug. It was not my ex, but one of his teammates. We embraced and I filled in the awkward silence with a nervous rush of shared memories. His surgery left him with an expressive aphasia so although he nodded and laughed, he could not speak. I felt hot tears on my cheeks as I watched this muscular, attractive, otherwise healthy man struggle.

His mom told me the story of how they got here. Her son had left his apartment in Texas one night and started driving. He did not remember the trip, but his parents later pieced together his route from gas station receipts in his car. At a truck stop in South Carolina, he had gone inside and written down his parent’s telephone number on a piece of paper. Not able to speak, he asked the attendant to call the number. His mom answered and, after talking with the gas station attendant, woke her sleeping husband and drove like a madwoman through the night to pick him up.

What was wrong with her son, my old friend, was an unresectable WHO Grade IV glioma. Otherwise known as a glioblastoma multiforme.

They had brought him directly to a local emergency room where he had scans and was in the operating room the next morning for a brain biopsy. Aware of Wake Forest’s status as a Brain Tumor Center of Excellence, they had brought him in for a consultation. Without realizing it, I had seen his brain MRI and pathology slides at that morning’s brain tumor conference.

By the time his mom finished the story, we were all in tears. They were crying for their son; he was crying for himself, and I was crying at the unfairness of it all. Why him? Why someone so young?

I felt my training rise up and try to shove the tears back, but I couldn’t stop. How had this guy, the one my friends had argued was the hottest guy on the football team, ended up here? How could a devastating tumor take away the voice of someone who was always talking trash around his teammates? I had seen his scan and knew his prognosis was grim. He looked at me and I couldn’t hide the truth.

When I realized that I had transcended the patient-physician boundary and instead sat firmly as a friend, I excused myself and left the room. I closed the door behind me and rested my back against the cool laminate, wiping away tears with the back of my hand. For a brief moment, I tried to chastise myself back into the professional decorum that was expected of me. I failed. I headed back to the physician workroom where my attending physician was waiting.

He listened attentively but after a few minutes, the tears reappeared, and I stopped. I couldn’t go on. “I can’t see this patient,” I said more bravely than I felt, “I can’t be a part of his care team. I know him and he was an old friend, and I can’t handle it.” My professor scoffed at first and tried to cajole me into coming back into the room. Buck up. This is part of the job. You’re eventually going to have to treat someone you know.

I shook my head and stood firm. I could not go back in.

I could not watch his eyes as his prognosis of less than a year was discussed. I could not read off the side effects of treatment and watch as he signed a consent form for treatment that would likely be futile. I could not watch a future turn to dust.

I never saw him again. I know he started treatment, but I rotated off the brain service and purposefully lost track of him. I didn’t ask the resident who came on the service after me, and I didn’t look for his obituary.

Twenty years later, I realize how unfair that was to him. How immature and unprepared I was. When I think about myself then, I try to give compassion to the young doctor that I was and work to keep a bit of that humanity showing now. Now, I have treated friends and some of them have survived.

But every time someone calls me seeking my help to cope with a new cancer diagnosis, I think of him.

It’s ok that you weren’t his physician, and it’s ok that the loss hit you so hard you took your grief away from what was already too much grief for the patient and his family to bear. There are problems with how we were trained, and there was no reason that “eventually” had to be that day. The patient-doctor boundary protects both parties, as both are humans, and it couldn’t be there in that case. Your piece made me cry for that young doctor you were who was made to feel like she’d done something wrong. Some things flatten us as people. It’s not a failure.

You did the right thing. Totally.