Hello everyone! I am putting the finishing touches on the first episode of Less Radical. I’ve been talking about Bernie Fisher for years and still felt chills when I heard the interviews, the music and the story come together. 😱

On September 25th, the first episode will be released right here! For those of you who are subscribers, it will be delivered to your email inbox. For those of you who are not yet subscribers, you can join now by clicking the button below. Or put a reminder on your calendar to check your favorite podcast app to subscribe.

Less Radical is an extension of what I try to do here every week - take the history, science, people and politics to explain how we experience of cancer. Thinking about the questions you ask in our consultations prompts me to examine my own beliefs and recommendations.

I have come to the conclusion that what we need is better screening and prevention, not sharper scalpels.

We understand so little of the biology of cancer that we are still treating it too late in many cases. And with non-specific, primitive treatments like surgery, radiation and chemotherapy. Few cancers have targeted treatments.

This was a choice we made in the 1970’s. We chose to focus on killing cancer cells rather than understanding the biology of what causes cancer to form. The good news is that we can make a different choice now. We can reject calls for more aggressive treatment and demand targeted cures. You can do this. I can do this. Together, we can demand that the diagnosis and treatment for cancer become MORE effective and LESS radical.

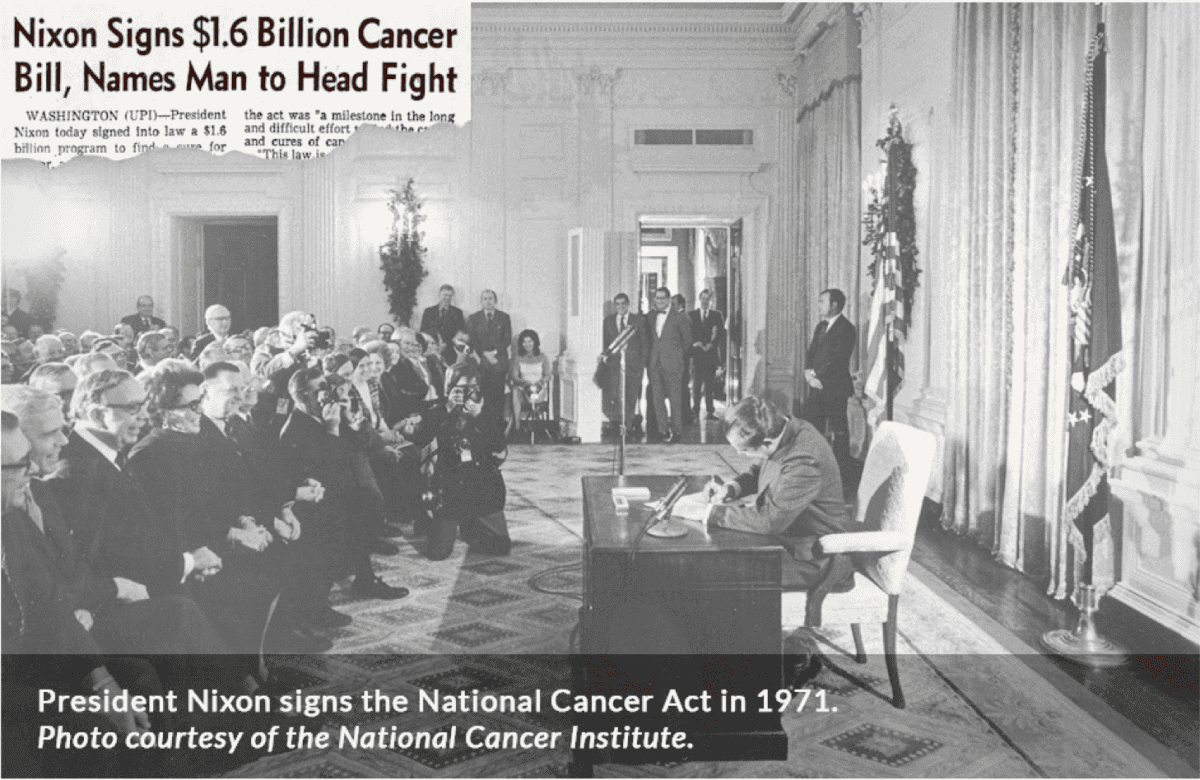

This week, I’d like to set the stage on where the podcast will begin. After WWII, the US government launched its first (meager) effort to cure cancer. I’ve written about the creation of the National Cancer Institute and the beginning of the quest to find a magic bullet for cancer. But it wasn’t until President Nixon that the government took an active role in funding cancer research. And it wasn’t even Nixon’s idea.

You know that saying that behind every successful man there is a strong woman? In this case, that woman was Mary Lasker.

I asked Mary Lasker’s biographer, Judy Pearson, to write a short introduction to Mary Lasker. Judy is an author and cancer survivor who you will here on the podcast. Her book, Crusade to Heal America, details how this unlikely New York socialite used her political power and passion to bring a very divided government together to pass the largest investment in cancer research in US history.

Funding from the National Cancer Act of 1971 provided critical funding for Bernie Fisher’s first clinical trials. It’s a remarkable story of how one private citizen moved the whole of government to her will. And how we all benefitted from her passion.

Next week, I share my thoughts on my first trip to Pittsburgh. But for now, join me in Washington, DC.

On his last day as president, Lyndon Johnson awarded Mary Woodard Lasker the Medal of Freedom. It is the highest civil honor the Chief Executive can bestow.

Johnson would not be the first of those in power – nor the last – to recognize what a force of nature she was. But medals be damned. Mary was out for cures to America’s debilitating disease. “I am opposed to cancer and heart attacks the way I am opposed to sin.” With that as her battlecry, this petite, well-coiffed socialite rewrote the book on American medical research. Her name may not be familiar, but her work continues to save millions of lives around the world.

Born in 1899, Mary was a feminist (ahead of her time) who used her femininity wisely. She was savvy, steely, and deliberate, with a goal of eliminating human suffering. And she knew how to play the long game to achieve that goal. To best understand the magnitude of her work, it’s crucial to grasp a little-known fact about America as the twentieth century unfolded.

While the country was a global leader in industry, transportation and communication, it lagged horribly behind the other developed nations in medical research. The infectious diseases that had plagued humans for centuries were coming under control. But tens of millions of Americans were affected by heart disease, cancer and stroke (more commonly known now as hypertension/high blood pressure). Combined, those three conditions were the cause of 71% of all deaths in 1940, and 51% of deaths under the age of 65.

When Mary married advertising legend Albert Lasker that year, one of their strongest bonds was a common mission to alleviate the suffering of others. They were tremendously wealthy, but as Albert explained to Mary that even his money would not be enough to make the kind of difference in medical research they sought. He knew where to get what was needed, however: Washington, D.C. Involving the federal government in medical research and education was a novel idea in the 1940s. And it was controversial. Furthermore, the alternative funding sources relied upon today (namely, national nonprofits) weren’t involved in research either at this point in history.

Under Albert’s tutelage, Mary also learned the art of swaying public opinion. After all, as an ad man, he did it for a living. He taught her the delicate nuances of “fund raising” – for political candidates – and “friend raising” – cultivating in those same politicians a passion for her cause.

Together they created the Lasker Foundation, awarding “seed money” to researchers on the brink of medical discoveries. (The awards became known as the “American Nobels,” and at 75 years-old, are still thriving today.) And in an ironic juxtaposition of interests, while Albert schooled Mary in garnering research funds, she shared with him her knowledge of fine art. Together they amassed one of the largest private art collections the country has ever seen.

Mary’s cause soon became her crusade. Legislators, medical experts, dazzling celebrities, even presidents and first ladies became the crusade’s powerful allies. At a time when women in the laboratories of the National Institute of Health (it was just one institute then) and the halls of Congress were an anomaly, Mary smashed Washington stereotypes.

Never having looked through a microscope, Mary Lasker did more for medical research than anyone before or since. Changing America’s mindset about medical research, she built a framework for it, and then procured the necessary funding from Congress.

Despite being what she called, “the grassroots rising,” Mary and her crusaders transformed the NIH from a single, poorly funded entity to the greatest medical research facility on the planet. The job was never easy, and those who were against her would not be kind. They labeled the crusaders as “Laskerites,” “the Health Syndicate,” “the Cancer Mafia,” “Benevolent Plotters,” and “Mary’s Little Lambs.” Cynicism and name-calling aside, their work became the most remarkably successful, yet nearly unknown, component of American history.

As Mary watched death statistics from heart disease and strokes declining, cancer deaths continued to rise. She was impatient with NIH’s plodding research. “Since nobody knows the full picture of cancer,” she complained, “how does anyone know what’s an unrealistic idea and what isn’t?” And then cancer became personal. In a cruel twist of fate, her beloved Albert died of colon cancer in 1952. Mary’s grief became gasoline on her crusade’s fire.

When Richard Nixon became president in 1968, Mary worried that he would be “a disaster of unparalleled proportions” when it came to medical research. She suggested to her crusaders that, in the shadow of the successful American moon landing, they should launch a “moonshot against cancer.” (Plenty of politicians have taken credit since!)

Mary persuaded her friend Senator Ralph Yarborough to propose a panel of consultants, charging them with making recommendations to conquer cancer. The panel was a clever mélange of scientists and lay people, Democrats and Republicans.

They presented their impressive and radical recommendations to Congress in December 1970. As Yarborough hadn’t been reelected, the young Senator Ted Kennedy took up the charge in January 1971, introducing the Conquest of Cancer Act.

The battles that ensued were fought on many fronts. Conservatives thought liberals wanted too much money for research (although when choosing its targets, cancer doesn’t discriminate between the groups). The scientific community argued over the cancer act’s proposed research path, not wanting too much government control. It was in the White House, however, that the quest to conquer cancer was nearly derailed.

Nixon’s greatest fear was having to face another Kennedy in the 1972 election. Preventing that scenario became his mission and the struggle that ensued – with the future of cancer research hanging in the balance – was rife with political intrigue.

The president made it known that he would not sign a cancer act with Kennedy’s name attached. Mary realized her only recourse was for Kennedy to step back and ask a Republican to sponsor the life-saving bill. A longtime family friend, Mary made the request, and the Senator from Massachusetts complied.

The ultimate result was the National Cancer Act, which funneled an extraordinary $1.3 billion ($8.3 billion today) into cancer research, turning the nearly always fatal disease into one that was survivable. Nixon called it his “Christmas gift to the nation.” Mary proclaimed, “He might just be the most sympathetic president we’ve ever had.”

We study history for a number of reasons, foremost of which is to learn from it, as it contributes to the fabric of who we are as individuals and a nation. The study also gives us greater understanding of, and appreciation for, the intrepid individuals who lived through its critical moments. Mary Lasker was one of those people. For five decades, this feisty and fearless “fairy godmother of medical research” positioned herself at the crossroads of politics, science and medicine.

She could have lived a life of carefree and unfathomable luxury. But in her biography, Crusade to Heal America: The Remarkable Life of Mary Lasker, we see a humble and generous human being, whose every waking moment of her ninety-four years was devoted to eradicating disease, easing suffering, and championing health education. “The purpose of medical research,” she once said, “is to allow us to die young as late in life as possible.” Mary Lasker did just that.

You can read more about Mary Lasker and order Judy Pearson’s book here. Or listen to Less Radical!