“How much radiation am I getting?”

This is by far the most common question patients ask me. Often this is couched in a concern that they are going to get “too much.” I must have answered this question a million times, but I’m always looking for fresh ways to address concerns about the treatments that I prescribe.

I was intrigued, therefore, when a patient suggested that I listen to an episode of Dr. Peter Attia’s podcast, The Drive. I’ve read Attia’s books and listened to a few previous podcast episodes. Attia interviews experts, asks smart questions and refrains from sweeping generalizations. He also operates without paid advertisements and therefore is not beholden to sponsors that promote wellness apps and questionable supplements. And he’s a surgical oncologist so he understands cancer.

The episode my patient recommended was a comprehensive conversation about radiation. In the intro, Attia admits that despite his oncology training, he doesn’t know much about radiation. So, he invited his friend and radiation oncologist, Dr. Sanjay Mehta, to educate himself and his listeners. His intro says it all:

I wanted to have Sanjay on the podcast to talk about all things pertaining to radiation oncology, but also the history and some of the misconceptions around radiation and radiophobia.

It’s fun to eavesdrop on two friends (yes, doctors are really this nerdy when we are together). I hope you have time to listen to the whole thing.

Most people don’t know much about radiation except what they see in modern culture…which TBH can be kind of scary - Hiroshima, Chernobyl, superhero transformations. And, of course, when there is an absence of information, it’s easy to let fear to fill in the gaps.

Below are my answers to common questions I get from patients and friends about radiation. I’m also open to an AMA (ask me anything) in the comments of any questions that you have.

(Caveat: I cannot give medical advice on any personal or specific situations. Those questions should go to your treatment team who have access to your medical complete medical record.)

What is radiation?

Radiation is a form of energy that moves as waves or particles (depending on how you feel about Einstein’s Theory of Relativity.) The radiation that I use to treat patients is called gamma radiation. Due to its high energy, gamma radiation is “ionizing” radiation which means it is strong enough to interact with atoms and cause them to give up their electrons and do things. Like damage a tumor’s DNA causing it to die.

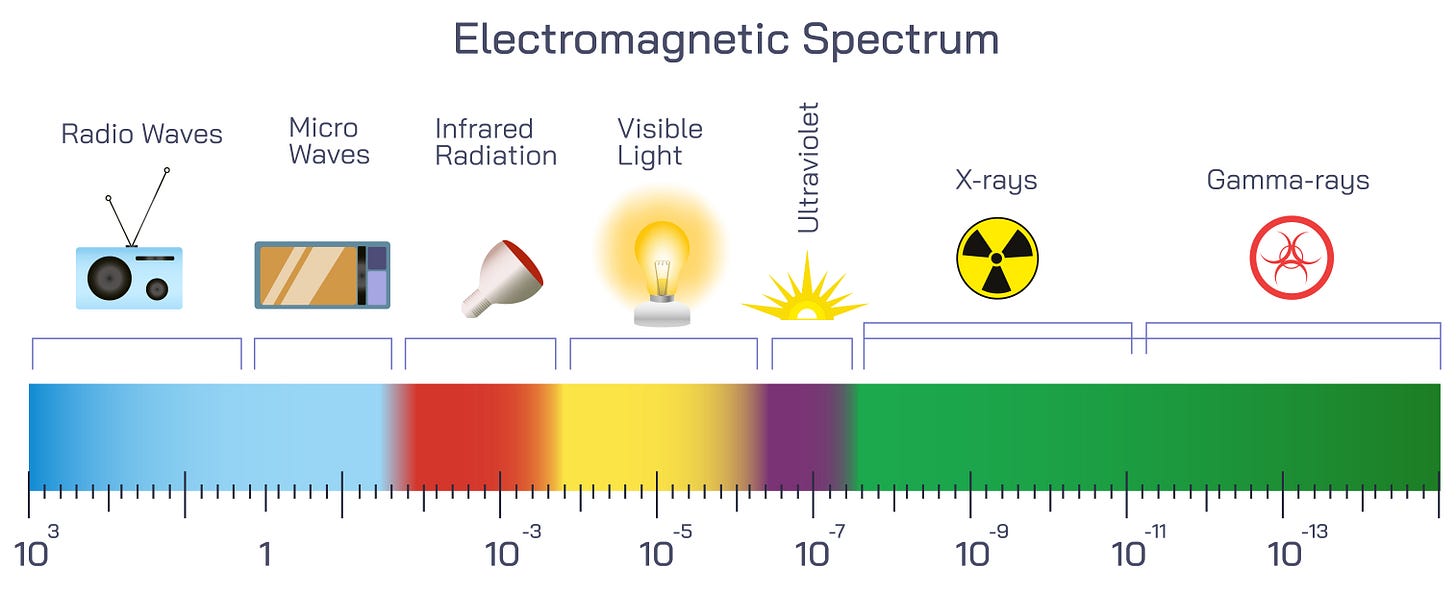

Weaker (or lower energy) forms of radiation include radiowaves, infrared light, visible light and microwaves. The light that you see right now coming from your phone or computer screen, for example, is made up of non-ionizing electromagnetic radiation.

In the picture below, you can see that electromagnetic radiation with low energy and long wavelengths is on the left side and travels long distances. Radiowaves, for example, travel miles from the station to our antennas. While high energy radiation like I prescribe is on the right.

As you can see, infrared radiation is towards the lower energy of the electromagnetic spectrum. Infrared radiation is non-ionizing, i.e. it doesn’t have enough energy to create change in anything it touches. It has less energy than a light bulb, for example. That’s why I tell anyone who asks that those weird infrared face masks that are all the rage right now are a scam.

How do you measure radiation and how do you know how much to give?

We measure radiation in units called Grays. Broadly speaking, solid tumors like colon, breast, prostate and lung cancer need higher doses of radiation - in the neighborhood of 50 Gy if given before or after surgery and higher doses (60-70 Gy) if radiation will be the only treatment. If we are treating a “liquid” tumor like lymphoma, as little as 4 Gy can be effective.

How we get to that total dose is called fractionation. This boils down to how many days patients will have to come into the cancer center. Patients obviously prefer as few trips as possible. Sometimes they will make suggestions like “How about three weeks?” or “My surgeon said you might be able to do it in a week.”

I can explain how I decide how many treatments to prescribe using a food analogy. Total radiation dose is like a pizza: you can cut the pizza into 4 pieces or 25 pieces but it’s still the same pizza.

Radiation is essentially the same. I can give you 50 Gy of radiation in 1 treatment, or 25 treatments of 2 Gy or 10 treatments of 5 Gy and so on.

Chemotherapy, when given at the same time as radiation, makes the radiation “stronger” (similar to putting baby oil on skin and going out into the sun) so we typically deliver radiation low and slow - low doses delivered over many weeks.

When targets are small and far away from any critical normal structures (say in early-stage lung cancer) we can deliver the treatment quickly, sometimes in as little as 1 treatment.

All of this to say that the number of treatments typically has no correlation to the severity of your disease (more treatments does not = more aggressive cancer).

I was doing fine with radiation until the end. Why?

Another aspect of radiation that many patients find surprising, is that the first 1-2 weeks of treatment, there are essentially no side effects from treatment. In the case of treating rectal cancer, for example, just because you don’t have diarrhea on day 5 does not mean that you won’t have it on Day 20.

Once again, a food analogy suffices. Delivering radiation is like cooking a turkey. (The patient is the turkey in this situation…sorry…but it’s the best I can come up with.). For the first few hours in the oven, there is little change in the turkey. Not enough heat has built up. It is not until the end of cooking (and even after it is removed from the oven) that the bird is fully done.

In a similar manner, patients may notice no changes for the first 1-3 weeks of treatment. Around the 3rd week, side effects can start to appear and will continue for weeks after treatment is over. The body (and tumor) will not show signs of radiation effect until they have received enough radiation damage to become clinically evident by either the tumor shrinking or side effects showing up or both.

The average time to pain relief for a patient receiving palliative radiation, for example, is two weeks after treatment is over. Their “turkey tumor” is still cooking despite being finished with treatment so I remind my patients to keep taking their pain medications and not feel disappointed if their pain is not completely gone on the last day of treatment.

OK, but you mentioned bananas. What’s up with that?

Another common misconception is that our radiation treatments or imaging tests are how most people are exposed to radiation. This could not be further from the truth. Did you know, for example, that a banana emits radiation? As do other humans. Radiation is part of our world, and it is helpful to understand the relative amount of radiation that each one of these sources emits.

Common sources of radiation exposure can be categorized into natural and man-made sources.

Natural Sources:

Cosmic Radiation: Most of our exposure comes from the sun. The amount of cosmic radiation increases with altitude and latitude.

Terrestrial Radiation: This originates from radioactive materials in soil, rocks and water. Most people are familiar with radon, for example.

Internal Radiation: This comes from radioactive materials that are naturally present in our bodies, such as potassium-40, which we ingest through food (including bananas) and water.

Man-Made Sources:

Medical Procedures: X-rays, CT scans, and radiation treatments for cancer.

Nuclear Power Plants: These facilities release small amounts of radioactive materials into the environment.

Consumer Products: Everyday items like smoke detectors, watches and some older paints contain small amounts of radioactive materials.

But what about those TSA screening machines?

In 2015, Vox put together this helpful summary of the risks of radiation exposure while traveling compared to other common sources.

Radiation exposure (unlike dose for cancer treatment) is measured in units called sieverts. The acceptable dose for a human per year is 20 millisieverts per year (50 for radiation workers like me). As you can see from the chart below, the exposure from any source of radiation in our modern world is pretty low.

You would need to travel back and forth from New York to LA, for example, twenty-five times per year to get close to the limit of 20 mSv. The beginning of the podcast covers this topic really well.

All in all, radiation is a safe and effective treatment for cancer when administered by a board-certified radiation oncologist. It’s also a HIGHLY regulated industry in developed countries - often requiring oversight from both state and federal agencies.

On my mind…

The Alexa Maxi Shirt Dress, Pony Club Print from Boden. Available here.

For breast cancer, I was supposed to have (I can’t quite recall, but I think this is the number) 26 sessions (same dose over more time). My radiation oncologist made a mistake and didn’t update my plan from 16. I ended up with 16 sessions. 5 months later (one lymph node removed during surgery 2 months prior to the start of radiation), I developed lymphedema. I can’t help but wonder if I extending the time that I took to “eat the pizza” would have been gentler on my tissues and helped me to avoid lymphedema. Thoughts?

It is a pity that they did not have more knowledge of radiation back in the 60's and 70's. As a result of so called safe radiation treatment back in the 70's in my late teens the results from my 40's on was life changing. Back then they used radiation treatment for non cancerous conditions and I had a course of radiation treatment for acne on my chin believing that it was perfectly safe. In my early 40's my thyroid gave up and my oral lichen planus started to become very painful making it difficult to eat. Then when I was 59 I was diagnosed with jaw cancer as a result of the lichen planus. Over time I have had a mandibulectomy and 2 maxillectomies all from a supposedly harmless treatment in my youth. If I knew then what they now know there was no way I would have had the radiation treatment.