I am excited to share with you a piece I wrote as part of my work on the ASTRO (American Society of Therapeutic Radiation Oncology) history committee. This committee highlights physicians who made immeasurable contributions to the field of radiation oncology. In this case, a doctor who sacrificed his own fingers.

Dr. Frank Ellis was a pioneer in administering a form of internal radiation called brachytherapy. His early work with radium led to the modern treatment of cervical cancer and he developed important formulas that are still used to calculate radiation dose today.

Interested in reading more about radium? Check out my piece on Why America Launched a GoFundMe for Marie Curie.

At the age of 5, Frank Ellis decided he was going to become a doctor. In school, he enjoyed physiology, disappointed that his chemistry lectures began with memorizing the periodic table. “I didn’t like memorizing isolated facts. I like things to be built up,” he later recalled. Ellis attended the University of Sheffield (UK) where an eye infection during his last year of training sent him to bed for almost two months in agonizing photophobia and pain. He ultimately graduated from medical school with honors in 1929.

The eye infection scrapped his plans to travel to Africa after medical school, so a friend passed along a job posting for the newly created position of radium officer at the Royal Hospital of Sheffield. After his interview, Ellis was offered the position and accepted. The job included six months of funding for travel to learn about radium and an annual salary of £600 (roughly $9,000).

In late 1930, the 25-year-old Ellis, still suffering from keratitis, left Sheffield for Middlesex Hospital in London where he learned to measure radium dose. He then embarked on a European tour through Belgium, Sweden, and Germany.

(It would not be until he was assigned to “poison gas” duty at Sheffield Hospital during World War II that he read about a new medication called sulfacetamide that could be used to treat people whose eyes had been exposed to nitrogen mustard. Although thankfully no citizens of Sheffield were ever exposed to the toxic gas, Ellis’ eight-year struggle with keratitis cleared up after five days of treatment.)

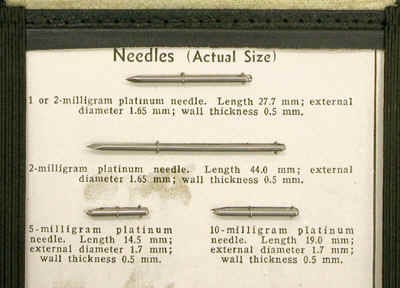

Upon returning from trip abroad, the energetic new radium officer was shown his new department, an abandoned operating room. Undeterred, he secured a table and a desk and then went about organizing the radium and looking for business. Through thoughtful observations of his surgical colleagues’ techniques and a deep study of human anatomy, Ellis became a passionate proponent of intraoperative and interstitial radiotherapy. He became an expert in the newest techniques and indications for radium treatment.

At first, Ellis struggled to find cases. Surgeons typically performed radium implants without much skill or knowledge. Ellis realized this but treaded carefully. He began visiting operating rooms to see where he might be of use.

One day while watching the chief of surgery “fidgeting about” during an oncology case and doing a poor job of placing radium needles, Ellis kept jumping in with suggestions. The frustrated surgeon finally stepped aside and asked Ellis if he would like to try. Recalled Ellis, “I did them all after that.” The chief of obstetrics and gynecology readily relinquished his cancer cases as well.

Ellis was soon performing radium implants every morning including most weekends for almost 12 years. (This near constant direct exposure later led to the amputation of most of his right hand due to skin cancers and other late radiation effects.)

Ellis planned each case using the tables included in a book he brought back from Germany. He even borrowed a portable x-ray machine from the children’s hospital to ensure his “spreader,” an early prototype of the Suit applicator we now use, was in place. Ellis followed his patients closely, learning as he went and dedicated one day each year to physically tracking down the dozen or so patients who had been lost to follow-up.

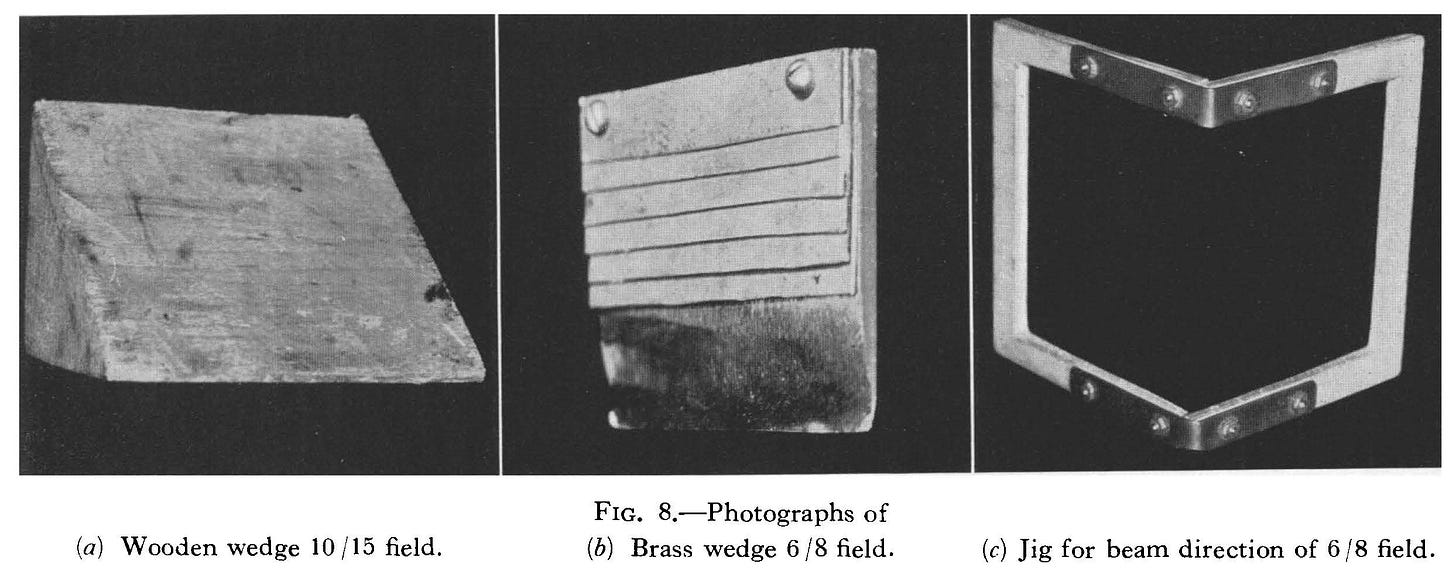

In 1934, Ellis began to use wedge filters made of wood and filled with rice flour when administering external radiation. This innovation allowed shaping of the radiation beam while ensuring a uniform dose distribution. He published his results a decade later. Any patient who has had radiation in the past 50 years, has had a wedge used in their treatment.

In 1943 and amid World War II, Dr. Ellis accepted a position as the first director of the radiotherapy department at Royal London Hospital. Concerned about the risk of contamination should a bomb hit the hospital, Ellis hired a moving van to transport their radium stock to a safer location. After the war, Ellis moved to the Churchill Hospital in Oxford, UK where he built yet another radiotherapy department.

It was during this time that Ellis also developed the concept of nominal standard dose (NSD), a revolutionary idea that for the first time allowed comparison of the effect of different radiation regimens on normal tissues.

Ellis drilled into the hundreds of trainees who came to study under him that any statement was open to questioning and that improvement was always possible. His graduate student and long-time friend, noted radiobiologist Dr. Eric Hall recalled “[Ellis] was always thinking of something new, and that exasperated his colleagues who were more set in their ways.”

He served as medical director at Oxford from 1950-1970 when he retired at the government mandated age of 65. Ellis is considered by many to be Britain’s most eminent radiation oncologist.

In retirement, Ellis served as a visiting professor at numerous institutions worldwide and received many awards for his contributions to the field of radiation oncology including the Order of the British Empire (OBE), bestowed by the Queen in 2000. At the age of 100, he received an honorary Doctor of Science degree from his alma mater, Sheffield University. Dr. Ellis died in Oxford, UK on February 3, 2006.

In a 1993, an 88-year-old Ellis sat for a videotaped interview. Midway through the conversation, the operator zoomed in on the tie worn by the aging physician. Repeating gold figures of atoms surrounded by the serpents of the medical caduceus cascaded down a navy silk background. The tie was a gift from the Hospital Physicist’s Association Ellis said and “represents my philosophy.”

The atoms, Ellis said, depicted science: “the only truth we are sure of.” The intertwined serpents, he said, represented “looking out for other people.”

In his long career of care and discovery, Dr. Frank Ellis passionately pursued both.

Thank you for reading Cancer Culture! I am so glad you’re here and I look forward to hearing from you in the comments below. Please click the subscribe button above to get Cancer Culture delivered to your Inbox every Monday afternoon. AND be one of the first to receive the podcast in September. To find out more about Dr. Fisher and me, follow the link below.

Why Him, Why Now and Why Me

In God we trust. All others must bring data. – Dr. Bernard Fisher By now, breast cancer seems to be everywhere–in our family, friends, social media feeds, and even the freezer aisle. In fact, the pink ribbon is so ubiquitous that some use the term “pinkwashing

References:

Cameron, J. (1993, September 7) AAPM history interview with Frank Ellis. AAPM History and Heritage. https://www.aapm.org/org/history/InterviewVideo.asp?i=39

Hall, EJ and Suit, HD. Obituary of Frank Ellis. Int J Radiation Oncology Biol Physics. 2006; 65(4); 963-4.

Pincock, S. Obituary of Frank Ellis. The Lancet. 2006; 367; 1050.