For a Father’s Day edition of Cancer Culture, I’m honored to lend this space to a very special person.

April Stearns was diagnosed at 35 years old with Stage 3 breast cancer that she found while breastfeeding her daughter. Four years later, April found herself struggling to “go back to normal” and find other young(er) people in similar circumstances. Finding few resources, she launched Wildfire Magazine where she now helps others “too young for breast cancer” heal through writing.

April’s story reminded me of the lessons that I learned from my dad. I hope it reminds you of someone in your life.

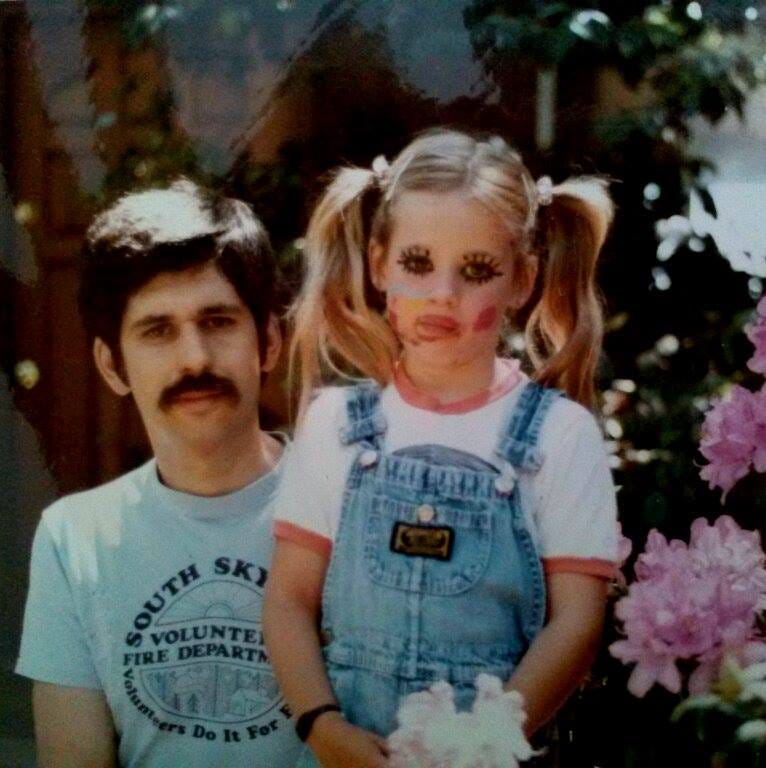

For 31 years, my dad juggled two jobs.

One required a suit, came with a salary, and took him away from home for 10 hours every day. It was understood that he was skilled and respected for this work but that it wasn't his dream job, nor was that important to him: it was the job that was required to keep a comfortable roof over our heads and food on our table. Nothing more.

He landed the job right after college and had it until he retired. Once or twice, I went with him to his office for Take Your Daughter to Work Day. He was a procurement manager for a large computer company in the original Silicon Valley when it was still dotted with orchards. Going there, I saw the beige walls and grey carpeting, the framed family photos lining his desk that my brothers and I gave him for Christmas.

I saw him "adulting" there with his colleagues and understood that he sat at that desk every day working on a computer, talking on the phone, making decisions for which he was responsible... I knew he came home tired and sometimes he went on business trips to places like Singapore and Ithaca, New York, but I never fully understood what he did there. I knew it didn't really matter though.

What mattered, what counted in the tally of universal good versus bad, and the oxytocin rush of following one's passion, was my dad’s second job.

He clocked into the second job the moment his silver F150 Ford truck rolled into our driveway each night, crunching the gravel under heavy tires, sending the dogs barking and us kids running to greet him. The second job wasn't dad, husband, or organic apple farmer, though he did those jobs, too.

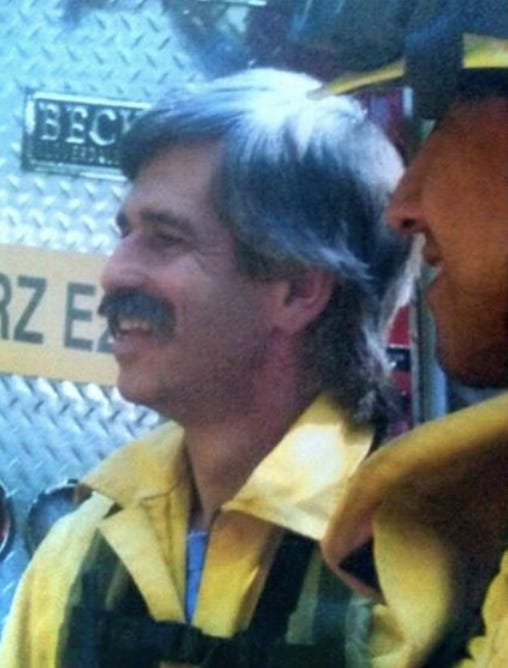

No, the other job that he was on the clock for from 6pm to 6am every night of the week, including weekends and holidays, was his role as chief of the volunteer fire department; a department that looked out for and protected our community from fire, medical events like heart attacks and rock-climbing falls as well as vehicle accidents in the Santa Cruz Mountains of Northern California.

Each weeknight, my dad would come into the house and exchange his dark suit and wingtips for jeans and work boots. On to his belt, he would clip a large red monitor, like an overgrown, heavy pager. It corresponded to a shiny black box that sat in the corner of our living room. Periodically the box would erupt in a series of ear-splitting high-pitched tones and beeps. These sounds would be mimicked by the monitor on my dad's belt.

After the tones, a dispatcher's voice would relay the incident information and the fire engine responding. If they called for Engine 21, my dad would drop whatever he was doing from wherever on our property and literally run for his gold-colored fire coat, pants, and helmet. I saw him do this drop-everything-and-run routine in the midst of cutting firewood, in the middle of dinner, on Christmas morning as wads of wrapping paper dotted the carpet. Most often, though, he’d jump and rush in the middle of the night when we were all asleep. When the tones sounded, he'd jump out of bed and into his fire gear, and then into the car and dash out the driveway.

This is what it means to be on-call. Hours later, we'd hear the crunch of the gravel as his car rolled back down the driveway, much slower than when it had left. He'd park and come in. Sometimes he'd tell us what had happened -- a motorcycle over the embankment, an elderly individual with difficulty breathing, a chimney fire. Sometimes he didn't say much at all, especially if it was a suicide or other fatality. If the call was a middle-of-the-night one, often he'd come in, exchange his fire gear for a shower and his suit and then head back out the driveway to a long day at the other job.

I learned about helping others from watching him.

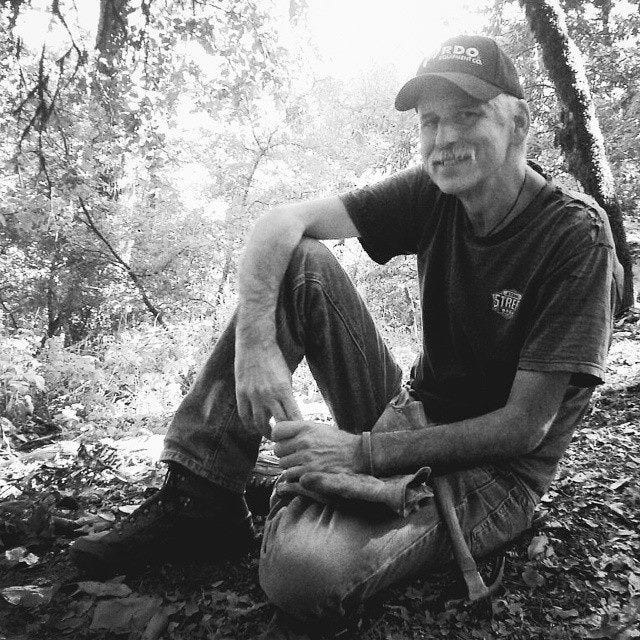

When someone needed a fire engine or EMT, he went. It was hard work, and I'm sure it was hard on his marriage, but he felt called to it, to ease another's suffering. In that way, I know it eased his own. That was his legacy to me. He taught me about helping others in order to learn to help ourselves. His work in the fire department made him whole. Everyone knew who he was in our community for his multiple decades of selfless service. When he died, the flags at all the fire stations in the area flew at half-mast.

A year and a half after he passed away from pancreatic cancer, and four years into my own survivorship from breast cancer, I launched a Wildfire Magazine (the name is symbolic for many reasons but is also very much a nod to my dad). After my diagnosis, I knew I needed to try to give others a roadmap in order to help myself find a path through cancer. When I made the decision to "stay in cancer" with my work, my therapist asked me if I was sure.

I had never been more sure of anything in my life, and eight years later, the answer is still a resounding “yes.”

Your dad sounds like a wonderful person and serving his community in that way brought so much to you and your work and I thank you for that and him

My perspective is that of a spouse. My children are all grown but in their mid 30s fortunately they have families they lost their father and I lost my spouse and when you said pancreatic cancer, that’s what we dealt with because he was in medicine. He was very careful he was not overweight had no concurrent underlying issues. Nothing that would make you suspect a thing all he had was indigestion and so towards the end of the pandemic because he had to lay up in bed and couldn’t deal with his patient sbecause he was so tired that sent him to his physician.

Before he could be treated, he had to have his Covid test, even though he was fully vaccinated for work and It was negative the next day he was in for CT scan. He immediately knew it was bad.

And a little more than three weeks later, he was dead

So Father’s Day is a tough one and I’m not over it yet. My kids suffer in their own ways. It’s been less than two years. It’s still so fresh because there was no chance for anything and with pancreatic it’s rough anyway.

Thank you for Letting me share as well