Last week I spoke at the Association of Cancer Executives annual meeting in New Orleans. The planning committee asked my friend Veronika and I to repeat the presentation we gave in Paris. The trauma of the recent truck attack in the French Quarter was still palpable alongside preparations for the upcoming Superbowl.

While we were there, a boil order went into effect as the city performed routine cleaning of the city water system. A minor inconvenience, the hotel staff shrugged. New Orleanians held discomfort and pleasure, tragedy and joy with an equanimity that reflected the tenuous nature of the city’s existence.

Still, it was strange to see partiers carrying yards of sloshing red hurricane cocktails walking past rows of elaborate mossy tombstones. It is almost impossible to not feel both alive and near death while you are in New Orleans.

On my way to the hotel, I asked the taxi to drive by now closed Charity Hospital. Three weeks after Hurricane Katrina, the governor of Louisiana announced that the 250-year-old institution would not reopen due to damage sustained by the storm and decades of problems.

Founded in 1736, Charity was the second continuously operating public hospital in the United States and served the indigent population of New Orleans until its doors closed. From a cancer perspective, Charity Hospital contributed large numbers of minority patients to cancer trials from 1970 onward due in part to its affiliation with Louisiana State University health system including the Department of Surgery which was led by Dr. Isidore Cohn, Jr.

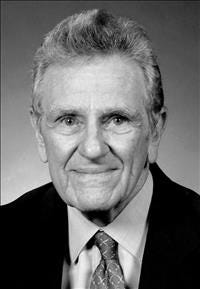

Isidore Cohn, Jr was born in 1912 to a prosperous New Orleans general surgeon and his wife. Cohn attended elite private schools, later completing college and medical school at the University of Pennsylvania. It was at Penn that he met another Jewish surgeon, Dr. Bernard Fisher. The two men formed a deep friendship which continued when Cohn returned to New Orleans to join his father’s practice.

In 1962, Cohn became the chair of the Louisiana State University Department of Surgery and chief of surgery at Charity Hospital.

An obituary written by a former resident described his manner this way:

“He did not tolerate foolishness and was a true patient's advocate. He thoroughly enjoyed his role as educator and as leader. It did not bother him to hold an opinion that might not be considered "mainstream." He was straight forward in his conversation and covered the subject matter without being chatty. There was often a twinkle in his eye and a hint of a smile on his face.”

My friend, Dr. Ed Levine, shared this memory of his mentor and colleague:

“When I took my first faculty job, I was at LSU in New Orleans, which was the home of Isidore Cohn. He was one of the half a dozen guys Bernie Fisher put together when they first put out the consortium to start the NSABP. There were several Jewish surgeons, which were rare at the time. These guys got together and said, gee, why don't we do something with this? Let's do some randomized and prospective trials. I saw some of the original letters from 1958, which, by the way, is still before I was born. These guys setting it up, what became the NSABP.”

Cohn was one of the co-authors of Fisher’s groundbreaking NSABP B-04 study which proved that more radical surgery did not offer a better chance of cure in breast cancer patients.

Cohn was a fervent supporter of the NSABP and unfortunately found himself on the receiving end of the first audit after a public announcement of data falsification by another NSABP surgeon in Canada. Cohn who had no idea there were concerns about the LSU data described the experience this way in an Archives of Surgery editorial in October 1994:

Because there had been no further communication regarding any problems in our participation in NSABP and because we had continued to enter patients into other trials, we were surprised to find two investigators from NSABP at my door early on Monday, March 21, 1994, with the message that they were part of an investigating team mandated by the NCI and that they did not know who or how many NCI personnel would be here or what they had expected to do or find. They had been told simply to bring a computer printout of all patients LSU had entered into any trials since 1971.

Ultimately, 11 members of an auditing team descened upon Charity Hosptial to review the twenty-year old records. They determined, as Cohn knew, that no fraud had taken place. Despite this, NCI press releases and media reports painted LSU as a bunch of sloppy researchers with shoddy record keeping. Cohn was incensed.

He wrote:

By conducting the audits in the public eye, and by releasing information repeatedly to the press without giving the investigators an opportunity to respond or even be made aware of alleged deficiencies, the NCI had put all clinical research into a questionable light.

By questioning the integrity of Cohn and his institution, the NCI placed unnecessary doubt in the minds of patients who had participated in the trials, made it more difficult to recruit patients into important trials and threw the conclusions of some of the most important studies in cancer care into doubt. This, charged Cohn, “has hurt the cause of cancer research, the very reason for the existence of the NCI, and ultimately has stimulated questions about the objectives of the NCI itself.”

Throwing out wild accusations in the midst of a deeply concerning scientific misconduct investigation was the exact opposite of the calm, detailed inquiry. Cohn did not endorse fraud but neither did he see the positive impact of casting doubt on every investigator due to one admittedly bad apple.

Listen to the entire story

The controversy soon blew over, but the impact on breast cancer research at Charity Hospital continued. It took months for clinical trial enrollment to recover which was difficult for Cohn who had worked so hard to ensure that his patients would be represented in these practice changing trials.

During his tenure as Chairman (one of the longest in the history of American surgery), Cohn transformed the LSU department from one staffed by part-time faculty and devoid of a meaningful research program to one of national and academic prominence.

According to Cohn’s biographer, he trained over 200 surgeons, was an early member of the American Association for Cancer Research (he joined in 1963) and held many prominent leadership positions including Vice President of the American College of Surgeons.

He was so beloved by his former surgical residents that they raised money to establish the Isidore Cohn Jr. Professorship of Surgery at LSU School of Medicine. Not satisfied, in 2002, his former trainees were major donors to build the Isidore Cohn Jr. Student Learning Center, a surgical training facility at LSU School of Medicine.

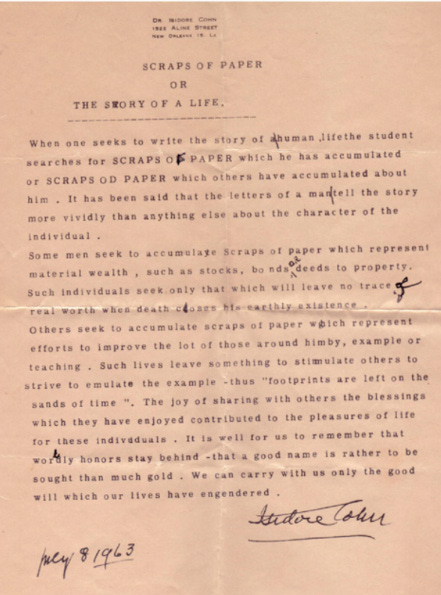

Like many great leaders, Cohn contemplated writing a memoir and included in his papers are his attempts. One moving example is an essay entitled “Scraps of Paper” Or “Story of a Life” which is dated July 8, 1963. It is included in his papers which are available at LSU.

Cohn sagely observed:

“Some men seek to accumulate scraps of paper which represent material wealth, such as stocks, bonds or deeds to property. Such individuals seek only that which will leave no trace of real worth when death closes his earthly existence. Others seek to accumulate scraps of paper which represent efforts to improve the lot of those around him by example or teaching…It is well for us to remember that worldly honors stay behind - that a good name is rather to be sought than much gold. We can carry with us only the good will which our lives have engendered.”

Judging by the love of his former students, Dr. Cohn accomplished that goal. I’m not sure that our political leaders feel the same way. It is up to us to remind them.

I love that old school rich history. I was a long time patient at the Cleveland Clinic and blessed to be a part of some really cutting edge things at the time in the ostomy care world. PS / After watching some of the confirmation hearings, by the way, I am convinced that neither “side” cares much about humanity.