This summer Dr. Veronika Panagiotou and I submitted a proposal to speak at the International Oncology Leadership Conference in Paris.

Our pitch was a 30-minute talk on comprehensive care for cancer survivors. In the audience there would be influential decision makers in oncology from around the world. What an opportunity to advocate for systematic change in the care of patients living with, through and after cancer.

I was elated when our talk was chosen to close out the conference which was held last week.

As the trip approached, Veronika and I practiced our talk via Zoom and adjusted our slides. I uploaded then changed several charts, hemming and hawing over which piece of data would be the most compelling. I was desperate to make the most of my time in front of this group.

My husband Todd and I arrived two days before the conference started, which gave us some time for sightseeing. Top on our list was a return trip to the Louvre. On our first visit many years ago, we saw most of the highlights. This time, I had written down the locations of a few pieces that we hadn’t seen before. As we entered the museum’s cavernous lobby, I was thankful for my list. Maybe we could see them all without getting lost?

On our way to the French crown jewels, I pointed out paintings that remind me of work.

While standing in front of this painting, a man’s foot caught my eye. In his meticulous attention to his model’s anatomy, had the painter captured an osteosarcoma?

Finally, we made it to the far end of the Richelieu Wing where the painting that I most wanted to see was displayed. I’d read about her in James Olson’s book, Bathsheba’s Breast.

James Olsen told the story of the painting this way:

In 1967, Dr. TC Greco, an Italian surgeon and art aficionado, took a spring vacation in Amsterdam. At the Rijksmuseum, he strolled through a section of Rembrandts, pausing in front of Bathsheba at Her Bath (1654). Hendrickje Stoffels, Rembrandt’s mistress, had posed for the painting.

It was not Greco’s first look at the work, but it was the first time he had used his surgeon’s eye. He detected an asymmetry to the left breast; it seemed distended compared to her right breast. He also detected swelling, or fullness near her left armpit. The left breast appeared discolored, and Greco saw what he thought might be “peau d’orange,” a pitted section of skin with the texture of an orange peel. All signs pointed to breast cancer.

With a little research, he learned that Stoffels later died after a “long illness.” He was confident, and conjectured so in an Italian medical journal, that she died of breast cancer.

Cancer. At the Louvre.

Our path out of the museum took us through the central sculpture garden. More than any other time that day, I felt like I was close to my patients.

Here, was Nike attaching wings to his shoes which reminded me of caregivers loading up bags to bring to all-day infusion appointments, trying to make the day go faster and perhaps be a little less painful.

And Prometheus lay chained to a mountain for eternity. Patients with head and neck cancer often tell me they feel trapped to the table as therapists click their masks into place. (A feeling

wrote about in her newsletter.)Finally, a lion violently attacked Daniel’s back. A reminder of what cancer that has spread to the spine feels when a patient must lie still on hard, metal tables either for treatment or an MRI. (As

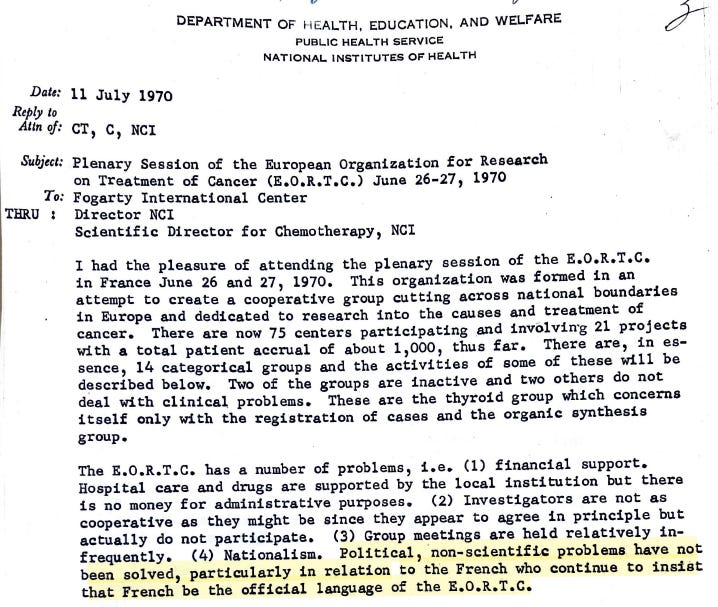

can attest.)In June 1970, the director of the NCI sent a representative to a meeting of the EORTC (European Organization for Research on Treatment of Cancer). The director hoped the group would join the NCI in efforts to find a cure for cancer.

After WWII, European countries had been unable to join the space race as they recovered from the war’s impact on their infrastructure and their citizens. Thirty years later, the US Government hoped Europe was now ready to enter this next “war”- one that would also require cooperative international efforts to win.

Unfortunately, what the representative found was disappointing. Beset by nationalism, lack of funding and an unclear organizational structure, the EORTC was a research organization in name only. I found this memo during my archival research:

Cancer is an international disease, and we rely on international partnerships to improve our outcomes. Unlike in 1970, European countries are often first to complete important clinical trials that doctors around the world, including me, adopt in our clinical practice.

Just a few examples:

In 2004, an EORTC trial was the first to show a benefit to adding chemotherapy to radiation in the treatment of head and neck cancer. (

lived this and more caring for her husband.)In 2005, a trial run by international investigators showed a dramatic increase in the survival rate of patients with glioblastoma multiforme, an aggressive brain tumor. This is still standard of care today. (

can speak to this personally)In 2025, a $42 million trial funded by the non-profit organization Prostate Cancer UK will answer the question: what is the best way to screen for prostate cancer. Like the trials that showed a benefit to PSA screening over 20 years ago, the results of this study will change how we screen and diagnose prostate cancer all over the world. (

‘s cartoons show the consequences of prostate cancer screening failure far better than me)

We don’t often share with patients the increasingly complex scaffolding of clinical trials that direct your care. But I can promise you that it is NOT comprised of research led solely by scientists or doctors in the United States.

As we move into a new era of leadership elected on promises of isolation and “America First,” we cannot ignore the possible impact on cancer research and care. For the first time in my career, I am hopeful about the promises of science to make treatment less radical and more effective. But that we cannot do alone.

"....but there's a sheet on the table." lol

What an extraordinary initiative with art not only imitating life as it must but also commenting on our preferred paths in medicine and sanctioned methodologies. As a cancer survivor I would not relish the idea of my own experience becoming a tragic opera whose libretto evokes euphoria but then why not? Perhaps we have reached an end of our victimization of spirit and our exhaustion within longs for a novel way of understanding.