There is a fascination about experimental work. In searching the unknown for new truths there is a mystery, and there is adventure and there is the thrill of discovery.

Dr. Gertrude Cox

I was reminded of trust a few weeks ago when I was a guest on KPRK’s Bibliocracy Radio. I, along with three Long COVID survivors, spoke about The Long COVID Reader. My essay about caring for cancer patients during the early days of the pandemic opens this collection of stories and poems.

Here’s what I wrote about trust:

As patients readily accepted my recommendations to shoot invisible rays into their most precious organs, some became unhinged when I mentioned a shot with a few molecules of sugar and water. Beloved co-workers refused mandatory vaccination and were gone. My responsibility as a doctor, a leader, and a trusted source of health information weighed even more heavily on every patient interaction as I plunged myself into unfamiliar science, learning and translating at the same time. I joyously exhaled when patients confirmed their appointment times and felt sharp stabs of failure when patients refused to engage.

How could we be in the same room and yet so far apart?

How could those who trusted me with their lives reject my pleas to grab the lifesaving opportunity in front of them?

As information on vaccine complications swelled, I wondered – should they?

In the face of a novel pandemic, the sausage-making experience of how science gets made was on full display:

Our well-defined roles shifted uncomfortably, and our precise departmental procedures were now in constant flux. We clung to anecdotal reports, waiting anxiously to discover our own fate. Absolute certainties one week were crazy conspiracy theories the next. Patients, now also potential vectors, flowed into our lives while our families were kept at bay. With their bald heads and bruised arms, the already wounded became more vulnerable and the well-crafted systems meant to protect splintered around us. The process-driven world of radiation oncology lurched forward into unfamiliar waters.

I certainly didn’t know how to explain what was happening. And it was impossible to educate the world, overnight, on the scientific method, virology and the basics of epidemiology. JUST TRUST THE EXPERTS was an easier message.

But that didn’t work.

People were dying.

Or maybe they weren’t.

Everyone wanted answers NOW.

Writers, journalists and physicians have written eloquently about the declining “trust in medicine” and “trust in science” more broadly. I understand the need to generalize but I’m not sure people distrust the basic tenets of science or medicine. No one is presenting the theory that little green men with wands control the function of our bodies. Or that gravity doesn’t exist. Or have started to use ivermectin paste to mend broken arms.

Instead, I think patients have started to distrust messengers including physicians like me. I base my recommendations on science - an ever-changing group of hypotheses and truths that are constantly being challenged through clinical trials and scholarly debate. Well-meaning friends and family may suggest care rooted in their deep love and concern. As far as I can tell naturopaths base their recommendations on a desire to use compounds found in nature.

The hard part about science is that it stands in stark contrast to the science I learned in my wonderful rural, public school district. Here facts were definitive and known. From the structure of the earth (crust, mantle, inner core and outer core) to what happens when you mix baking soda and vinegar (🌋), our teachers and textbooks had an explanation for everything.

Real science IS about the answers to complex problems. But almost more importantly, science is also about how we arrive at those answers. The scientific method provides the structure of how we test the new against the old. Not through opinion or feelings, but by impartial comparisons.

Through my training, I’ve seen the best results by following science. I believe in clinical trials because I know they are built on strong foundations of statistics. The best trials are built on statistical methods that remove bias in order to give the truest answer to “what is the best thing to do in this situation.” I trust the science because I understand how the science sausage is made.

One of the most influential people on our modern approach to science was North Carolina State Professor of Experimental Statistics Dr. Gertrude Cox.

Gertrude Cox was born on January 13, 1900, and grew up on a farm in Iowa. She worked briefly at an orphanage in Montana and returned to Iowa to get a college degree so that she could manage the orphanage fulltime.

To help pay her tuition, Cox worked as a computer in her math professor’s lab. In the 1950’s, a “computer” referred to a person, usually a woman, who performed math calculations on hand operated machines. Cox discovered she loved math and switched her major. After graduating, she studied at University of California-Berkely before returning to Iowa State as an assistant professor in 1939. A chance train ride led her to North Carolina.

The president of North Carolina State College (later NC State University) and Cox’s mentor at Iowa State College were sitting next to each other on a train ride. The president asked for recommendations for someone who could start a statistics program in North Carolina. When Cox’s mentor returned home, he gathered a list of ten qualified men and asked Cox to what she thought. “What about me?” she asked.

He agreed and wrote to the president “These are the ten best men I can think of, but if you want the best person, I recommend Gertrude Cox.”

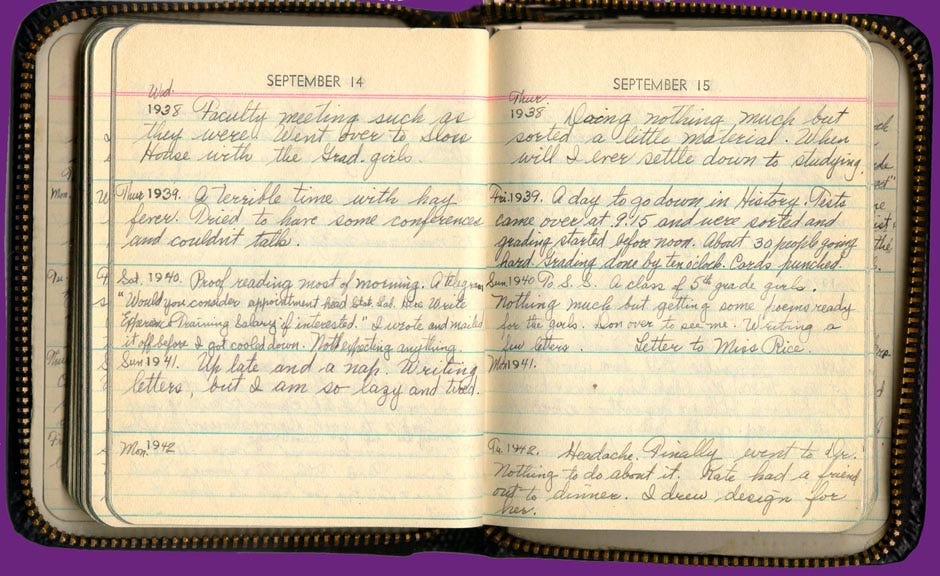

Cox received a telegram offering her the job on September 14, 1940. She noted in her diary “I wrote and mailed it off before I got cooled down. Not expecting anything.”

Cox arrived in Raleigh a few months later. She was the first female full professor and the first female department head at NC State. Her department supported the research of professors as well as state agencies. Whatever the assignment, Cox demanded that her faculty and students plan “the experiment so that the statistics collected will be easily interpreted by the average reasonably intelligent person.”

At the time, systematic errors in research were common. Scientists commonly picked and chose which subjects to include in their research. For example, Cox evaluated a controversial study on the benefits of kindergarten. The study left out an important school that would have changed the results dramatically. Her comment to the investigators was “you could use a great deal more help from qualified statisticians.”

Cox co-authored the classic statistical textbook Experimental Designs in 1950 which served as the definitive reference to plan and execute scientifically sound experiments. Software now performs these complex calculations, but through the mid 20th century researchers referenced the hundreds of tables in Cox’s book in order to plan and execute their trials in statistically proper ways.

As I read about Cox, I was reminded of my colleagues who dedicate their lives to clinical research. I thought about the cadre of statisticians who help them plan clinical trials and are the first to deliver the bad news that a treatment they thought would be better, isn’t.

It takes months for a randomized clinical trial to be approved, years to collect patients, years to analyze data and then months for publication. Many clinicians will only complete a few clinical trials in their lives due to the amount of work (aka bureaucracy) involved. I have watched this process throughout my career and the steady determination it takes to propose trials and grants, face rejection and then get back up again.

Because of the design process started by Dr. Cox and implemented by medical researchers all over the world, I trust science. And I hope you do too.

On my mind…

From This American Life:

Psychiatry used to be all talk. Then came a patient named Ray Osheroff.

What happens when the people you trust to make you better, don’t?

Fantastic piece, thanks so much!